Tourism | Industry | The Sea | Agriculture | Golf

During the earlier part of the period, tourism played a major role in North Berwick life

In the early years, many competitions were organised by the town council on the golf courses, on the beaches where children built all manner of things in sand competitions, in the yacht pond where model boats were judged and raced and in the pool where there were regular galas. The putting courses were kept in top class condition and were arguably the finest in Scotland thanks to the efforts of two burgh course greenkeepers transferred one to each green for the summer from their usual duties.

Anne Cowie

The previous statistical account covered the period in North Berwick which saw the end of the London society annual relocation to North Berwick, but the large mansion houses which they had built to the east and west of the town remained more or less intact until the 1970s.

The immediate post-war period, say from 1950-65, saw North Berwick as the annual holiday Mecca for the city dwellers of Edinburgh and Glasgow. The first two weeks would find the town full of Edinburgh trades holidaymakers and the second two weeks their counterparts enjoying the Glasgow Fair. In 1953 there were 39 hotels and boarding houses providing full board, three meals per day interspersed with the healthy pursuits of golf, walking and bathing in the sea or outdoor unheated swimming pool. 3000 would attend a children’s swimming gala and 700 would pack into a Saturday night dance in the harbour Pavilion. So many passengers thronged the outbound trains at the end of Edinburgh and Glasgow holiday that it took two steam locomotives to pull them up the incline to the gasworks.

The landlady played a pivotal role in the tourist industry; here Douglas Seaton summarises his interview with Mrs S. Skwara, formerly Miss Young, proprietor of Fairhaven, 20 Melbourne Road, for 53 years.

In the 1950s, the summer season in North Berwick lasted from late May until September, and the guesthouse landlady with her welcoming smile, attention to detail, and friendly manner was an integral part of the success the town experienced during its heyday as a holiday resort.

The landlady was part of a team, normally supported by her family, working from 6am until midnight during the season. The elderly visitors arrived in June to enjoy the peace and quiet, before the Edinburgh trades fortnight in July. By the time the Glasgow accents could be heard during the second half of July, the summer season was in full swing. August was the period when the factory workers from Paisley arrived, and the English school holidays began.

In the 1950s, full board was the standard fare, which included breakfast, lunch, ‘Scottish’ high tea, and supper. The guests stayed for a week or a fortnight and the majority booked family rooms. The glossy brochures enticed the visitors with slogans such as ‘H&C basins in every bedroom’. It worked, they came in their thousands from all over Britain.

The landlady’s day started at 6am in Brodie’s bakehouse situated in the courtyard through the close at 13, High Street. There, the freshly made rolls and bread, still warm from the ovens were collected. On the way home she would pass the horse and cart from the Bass Rock Dairy delivering milk with an inch of cream on top, and the freshly laid eggs from the Heugh Farm.

In the days before frozen vegetables, the meals had to be freshly prepared, including homemade soup, pastries and plenty of apple pie for the guests to have a second helping. All the provisions were supplied daily from the local butcher, fishmonger and greengrocer, delivered by a message boy on his bike. Sometimes the menu was hastily altered as produce was unavailable, but the landlady was accustomed to shortages following years of rationing. On Friday fish was available for those with a particular religious persuasion, and the bacon was discreetly removed from the breakfast plate. The guesthouse linen was sent to the laundry in Dunbar Road, and returned the following day. During the busy part of the season, the laundry helped out by offering a three times weekly service.

In the evening the guests would gather on the wall in Melbourne Road enjoying the last of the day’s sun, as they waited for the sound of the gong from their respective guesthouses. The children all wanted to strike the gong, and jelly and ice cream was their favourite.

With fewer motor vehicles around, the children could safely cross the road to the beach. The activities organised for them included sand castle and model yachting competitions, and swimming galas in the outdoor pool. The Seaside Mission encamped on the beach opposite the Victoria Cafe was always a good sing-a-long, and fishing off the harbour entrance for a ‘podlie’ or two, filled an afternoon. Few guesthouses had a television, and the families enjoyed the twice-nightly pierrots’ variety show at the harbour Pavilion. Mr. Halkett’s bus trips were popular when granny stole ‘forty winks’ travelling round the countryside. No holiday was complete without a sail round the islands in one of David Tweedie’s boats, or hiring a rowing boat in the West Bay from Mr. Pearson. With the putting greens, children’s golf course and tennis courts, there was plenty to keep everyone occupied, and on a rainy day the cinema opened especially for the visitors.

During the 1950s, the guests were mainly working-class families from all corners of Great Britain. Later the number of families visiting from Europe, America and Canada increased. A family from the Rockies arrived in North Berwick and, having never seen the sea before, was not convinced when told by the landlady that the sea rises and falls with the tide. They were given the room with a balcony overlooking the beach, and the family stayed up all night just watching the sea ebb and flow.

The story of the German couple that booked in for one night, and stayed for a fortnight is typical of the friendly manner in which the visitors were received. Many families came back year after year to the same guesthouse and the landlady watched as their children grew up. Often Christmas cards were exchanged, and these friendships lasted long after the landlady retired. By the time of the Glasgow holiday weekend at the end of September, the gas street lighting had been switched on. The lamplight dipped and spluttered as the pressure fluctuated when the guesthouse cookers came into action, signalling the end of a long but rewarding season.

The mid 1960s saw a substantial change and though visitors still came they were now tourists with cars who stayed for a shorter period and drove on to the next attraction. Their children, the post-war baby boom, had already found the delights of European package holidays, the dependable Mediterranean weather and the freedom which social changes engendered.

North Berwick soldiered on oblivious or unwilling to change, or see the need for change. Bed and breakfast, bar meals and other down-market developments were shunned and the season contracted as the post-war parents eventually joined their children in European resorts. But the writing was on the wall and fire regulations in the 1970s gave a lucrative exit for those hotel and boarding house owners faced with the substantial expense of complying with the fire regulations or the escape route of converting their large properties into saleable flats. Many took the conversion alternative, many of them were anyway of an age to retire.

Bed and breakfast came eventually of course, although perhaps more by change of ownership than change of practice among the traditional owners. There are only six hotels left, no boarding houses and only a handful of bed and breakfast establishments. There are a few self-catering units but relatively few compared with the demand and the much larger provision 50 years previously.

Looking north along Quality Street, North Berwick, 1960s, with Melbourne Place in the distance. Tucked in beside the cloak room and toilets was a tourist information centre. Gilbert’s was one of three garages in the town and the site is now occupied by flats.

But this is infrequent and not really catering for tourists. The July peak has gone; indeed many local traders now take their holidays in July because the town is so quiet. The business comes now principally from golfers in May, June, September and October, and from English holidaymakers in August. There is a steady trickle of European and North American visitors throughout the year and any major event in Edinburgh, for example the Edinburgh Festival, will cause substantial demand for accommodation in North Berwick by virtue of proximity and the 30-minute train service to the heart of Edinburgh.

It would be hard to argue that North Berwick is any longer a holiday resort. It is essentially a retirement town and a commuter town for Edinburgh. The bulk of building in recent years has been new housing and although there has been some infill of shops, there have been no new hotels built for many years and a steady disposal or conversion of the old ones.

After the end of the second world war, serious attempts were made to restore the pre-war holiday resort image the town had gained with, it has to be said, some success. Our population around this time was about 4000 and the months of July and August in the fifties saw this at least double with summer visitors mainly from Edinburgh and Glasgow. Boarding houses, hotels and private houses all catered for these summer arrivals. The grocers – Edingtons and Cowans acted as agents to try to satisfy the needs of the visitors and those prepared to let their premises complete or in part. Trains (still steam) arrived loaded with these holidaymakers to be met by numerous taxis from Gilbert’s, Russell’s and Fowler’s Garages plus a taxi firm of Bertrams. All provided at least three cars which could deliver one hire then swiftly return for a second. The fare for an address in town was two shillings and sixpence and to the Rhodes or Gilsland caravan sites three shillings and sixpence (12.5 and 17.5 pence).

Anne Cowie

Caravan and camping – Bill McNair recalls the growth of Gilsland

The short history of tourism in North Berwick goes along the lines of the birth and growth of Gilsland. I was brought up in Leith, my father as a doctor in Ferry Road. We had a holiday bungalow in Broadgate, Gullane, and all our weekends and holidays were spent there, exploring Gullane, Dirleton, North Berwick and Dunbar. Most people in those days (the early 1930s) worked a six-day week and had one week’s trade holiday in the summer and one day off at New Year (not Christmas). Their holidays were spent walking, cycling, or by tram to Portobello where all the fun and games were along the promenade. The more adventurous went as far as Prestonpans and they walked the rest. Seaton Sands was a shantytown of huts and buses etc. and those who couldn’t get accommodation used to rent a tarpaulin and buy some straw from the farmer, and the family camped out like that for their week’s holiday.

As you went down the coast you came to Gullane, the holiday place for the more fortunate, the professional class businessmen, ex-army and navy officers, retired clergy, doctors etc. There were a few council houses, several upmarket hotels and lots of holiday houses that were lived in for most of the year. Gullane, of course, was serviced by trains, having its own railway line and station and buses and the holiday inhabitants had their own cars and many even had their own chauffeurs.

Then you came to North Berwick. This was the chosen town for the important people, lords and ladies, prime ministers, MPs and even kings. It had its own railway line and station and the London train stopped at Drem so that the sleeper carriages could be shunted onto the North British line. North Berwick had several large garages specially to service and stable their chauffeur-driven cars, and of course lots of minor accommodation for the chauffeurs and servants. Those who weren’t fortunate enough to own big summerhouses up the Avenue or wherever could rent a house or bungalow for the summer. Many of the traders of the town had at least two abodes – one above or close to their shop or working premises where they stayed all summer, and a substantial house or bungalow that they let out for the summer and moved back into for the winter.

The exception to this was two farms, the Heugh and the Abbey.

Pre-war, the Heugh was a dairy and poultry farm at the top of the Heugh Brae. It had a field adjoining the Law with a ‘doocot’ in the middle and on the periphery of that field were several holiday huts and buses where people enjoyed their holidays. The Abbey farm was a dairy farm at the telephone exchange and its field lay to the west. One field was called the Mason’s Apron or the Green Apron field, and in that field adjoining Grange Road were two holiday abodes. One was a wooden hut owned by George Woodburn and four other chaps, and the other was an old bus body, turned into a caravan owned by the Stewarts, Mr and Mrs Stewart, Jim, Alan, Terry and their two sisters. These were used faithfully at all holiday times.

One day in the early 1930s, my father was driving along Grange Road and noticed that the old fever hospital looked as though it had been abandoned. He contacted the county council and asked if he could buy it. His idea was to convert it into a holiday home for his patients in Leith. The council sold him it and not long after the Abbey farm came up for sale so he bought ten acres opposite to keep hens and ponies.

My grandfather looked after the place and the holiday home took shape. It was so successful that they started to copy the Heugh and the Abbey by putting old buses, single and double deckers, trams and even railway carriages on the chicken field. Then the second world war came along and Gilsland was used for evacuees. They soon went home, so the place was filled up with airmen.

My father and I went to war and on demob we started up where my grandfather had left off and instead of old buses, trams and huts, people started to turn up with huts on wheels, vans converted into caravans, and tent trailers. Everyone wanted holidays, weekends and now two weeks in the summer. There was a lot of animosity against this in North Berwick and the town council tried to stop it. But Gilsland was outside the burgh and the county was quite happy with it and Gilsland got busier. The town council then thought they would get in on the act and started to take in caravans on the car park next to the rugby pitches. This was a great success and we both did well as more and more people could afford a few days off work to relax. Then a Mr Muirhead bought the Mains farm at the top of the Law Brae. He saw all the caravans going along Grange Road to Gilsland. He started up showing them into his field next to his house. By this time, the town council had moved their site from the rugby pitch to Lime Grove.

Caravanning got busier and busier and, in 1959, the government introduced the Caravan Act and minimum standards were set, ie number of toilets, roads, fire points etc., etc, which we all had to comply with and cost a great deal of money. Yet caravanning became so popular all over the country and especially at North Berwick, the government raised the minimum standards 100% within two years, and in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s it was hard work catering for many caravanners’ every needs. Then the cheap air fares to sunny places and package holidays took over and the touring caravans started to decline, and the people changed to static holiday caravans. They took their main holiday abroad in the sun and had their weekends and any other free time at their static caravan.

This trend seems to be the norm nowadays. Most if not all of our clients go abroad for the sunshine at least once a year and for the rest of the year they like to pop down to North Berwick for golfing, walking or diving etc., at weekends or short stays. They want to be able to drive down or come by train or bus and pop into their caravan that has all the mod. cons. without the harassment of towing it. So the caravan is now their country home where they can get away from it all and relax without too much hassle or stress.

There has been a long tradition of boat trips to the islands near the town, particularly to the Bass Rock and Fidra. After the war this started up again with at least three boats in regular use. These were the Britannia, St Baldreds and St Nicholas which each took up to 40 to 50 passengers. They had been commandeered as picket boats in Scapa Flow during the war but survived to provide peacetime service for over ten years, run by Alec Hutchinson, his son Ronnie and David Tweedie. In suitable conditions during the summer there would be a trip round the Bass every 30 minutes as well as frequent trips to Fidra.

Since about 1960, only Fred and Chris Marr have run regular boat trips to the islands, and they continue to do so using their second generation Sula, which takes up to 72 passengers. As package holidays abroad developed in the 1960s, fewer visitors stayed in North Berwick and the demand for boat trips also declined. However, there continues to be substantial numbers each year for whom a trip to the Bass to see the gannets is an unforgettable experience. Most boat trips go round the Bass (and sometimes Craigleith) with only a few visits to Fidra nowadays where a short landing is only possible in the right sea conditions. Landing on the Bass requires permission from the owner and is usually restricted to organised parties.

Getting visitors on and off boats can be a tricky business especially when they are elderly. With the harbour dry at low tide it is necessary to use the exposed outer jetty (the old pier) a lot of the time, while landing on the Bass can be difficult even in calm conditions. Weather can deteriorate rapidly so good planning is essential. It is a great credit to the different boatmen who have operated over the years that none of their many tens of thousands of passengers have been lost or suffered serious injury.

Local boats serviced the lighthouses on the Bass and Fidra until these went automatic in 1988 and 1971 respectively. This would typically involve two or three visits a week, taking out food, fresh water, equipment etc as well as conveying the lighthouse keepers. Wives and families of the three keepers lived on Fidra, which was designated as a ‘shore rock’ but not on the Bass (a ‘sea rock’) where only the keepers resided. A Mrs McFie is remembered for providing teas and scones for visitors who landed on Fidra.

The Scottish Seabird Centre has proved to be a success for the town. In 1992, East Lothian District Council launched a Harbour Area Study. Partly in response to this, Bill Gardner, then vice-chairman of the North Berwick Community Council, suggested that the spectacular Pavilion site should be the location for a Scottish Seabird Centre, using new technology to interpret the life cycles of the twelve species of nesting seabirds (over 350,000 birds) on the nearby islands, including most importantly the vast gannet colony on the Bass Rock. He envisaged using remote TV cameras and transmitters on the Bass Rock and other islands together with multi-media and other facilities to create a world-class visitor centre. With the help of a small grant he compiled a comprehensive feasibility study setting out how such a centre could be created.

After several false starts, a small group consisting of Bill Gardner, Sir Hew Dalrymple (whose family has owned the Bass for almost three centuries) and David Minns of the RSPB investigated the possibility of obtaining lottery funds. In 1995 an application was submitted to the Millennium Commission and followed by a full bid in 1996. This was well received by the commission and the project then took off with the formation of a charitable trust, later chaired by Rear Admiral Neil Rankin. Financial help from East Lothian Council and Lothian & Edinburgh Enterprise enabled the design and business planning to be undertaken and the further funding needed for the construction and equipment was raised from a wide variety of sources. Local help included a major landfill tax contribution from Viridor and donation of cement from Blue Circle at Dunbar as well as a local quarry company which provided the stone for the external cladding free of charge.

An innovative and attractive building has been constructed and fitted out at a total cost of £3.7 million and was opened on 21 May 2000 by HRH Prince Charles. The centre includes a shop, cafe and small cinema as well as extensive interpretation about the natural history of the offshore islands. As originally envisaged there are close-up pictures of seabirds from remote cameras on the Bass and Fidra as well as a viewing platform with telescopes looking out to the islands and along the coast.

The Scottish Seabird Centre is a charity that aims to increase awareness and appreciation of Scotland’s natural environment. In its first 15 months, the centre has attracted almost 250,000 visits and injected more than £1 million into the local economy. It has already been awarded several civic, architectural and environmental awards and is a tremendous asset for North Berwick, East Lothian and Scotland. A new attraction was opened in November 2001: a video link to the Isle of May to view seabirds in the summer and breeding grey seals in the winter.

It has more than lived up to the hopes for its popularity and continues to provide much pleasure to both locals and visitors alike. The building design, by Simpson & Brown, has been well received and has had much acclaim architecturally.

Norma Buckingham

Industry

In spite of proposals (1960s, 1970, 1972) to build factories and expand small industrial estates in North Berwick, only a few industries persisted.

In March 1958, it was announced that Ranco Ltd was to take on a seven-year lease of the former Admiralty buildings at Castleton/Tantallon (Canty Bay). The following month, Ranco Ltd ‘makers of thermostatic controls…and rotar units for refrigeration etc’ was advertising for senior and junior engineers for the design and development of small rotating electrical machines in the FHP range, to work at the company’s development laboratory at North Berwick (Haddingtonshire Courier 1958 June 18). At this time Ranco was the largest producer of motors in the United Kingdom. In 1962, the production moved to Haddington while the development work continued at Castleton. Due to American trade restrictions in the 1970s, the UK division became Lothian Electronic Machines (LEMAC). The development and research work stopped at Castleton in the 1980s and the company operations were consolidated in Haddington and Livingston.

The site was again listed as vacant in 1983; by this time, it was the Ministry of Defence that was listed as the owner. In 1984, the council extended the planning consent to include light industrial research and development purposes, and Ferranti took over the site (East Lothian Courier 1984 September 7), purchasing it outright from the MOD. By 1991, following a fall in the amount of defence-related work available, it seemed that the GEC-Ferranti testing plant (employing 23) was to close (East Lothian Courier 1991 October 11). In the early 1990s, DERA (the Defence Evaluation Research Establishment) a part of the MOD, leased the site for a few years from Ferranti; it seems that, to the end of the period, ownership was retained by Ferranti.

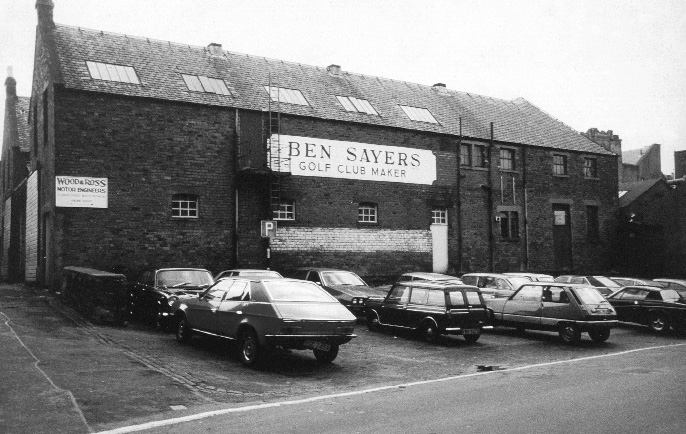

Old Ben Sayers factory, Forth Street, North Berwick. By the time this photograph was taken in c1983, the

factory had been relocated for nearly 20 years

In 1964, the long-standing Ben Sayers firm – manufacturers of golf clubs – moved to their new factory in Tantallon Road. The business was sold to Grampian Holdings, then in 1998 to the Caledonian Golf Group. In 2003, it was announced that the Ben Sayers factory in the town was to close – after 124 years.

New Ben Sayers site in Tantallon Road, North Berwick, 1964

There were a few other industrial developments of any size:

Robertson Textiles built their factory in Heugh Road (designated an industrial park). KEX, then Initial Towel Co Ltd – a large employer – moved to Tantallon Road.

Wilco Sports manufactured fishing tackle; they appeared to have closed by the end of the period.

The sea

The period since the last war has seen the continued slow decline of fishing as an important part of the local economy, a decline that started towards the end of the 19th century. Before the last war, fishing with long lines was widely used – this involved baiting perhaps 600 hooks on a line which was left on the sea bottom for about two hours before being hauled in. Haddock, whiting and cod were the main catch. This continued for a while after the war but it became increasingly uneconomic and after a few years there were insufficient fish left to catch in this way. Bigger boats operating further offshore took over the catches of white fish. For some years visitors were taken out in small boats to fish for mackerel but there have not been enough fish for that to be worthwhile in recent years. One factor, which is thought to have contributed to the decline of fish stocks, is trawling for prawns – the small mesh net that is used scrapes along the sea bottom and can kill a lot of small fish. This started after the war and still continues, though not from North Berwick.

After the war there were six boats fishing out of North Berwick each with a crew of two. At least eight fishermen made a full time living out of crabs and lobsters using about 80-90 creels each and there were additional part-time jobs as well. Nowadays there are only four boats operating with 200 creels or more each, providing part time employment only for up to six fishermen – an indication of the decline in crabs and lobsters. In the 1950s and 1960s it was not unusual to find three or four lobsters in one creel – which would be unheard of nowadays. Mechanical winches have made it easier and quicker to haul in and check the creels so that more can be handled; the result is that there is now more fishing pressure on stocks even though there are less boats operating. Lobsters are less abundant than in the past and crabs have become very scarce in the last few years. Creels are put out all year round when the weather allows but catches are less in the winter though the catch is then more valuable. Lobsters and crabs go to holding pools in Dunbar before being sent abroad to France and Spain. Only a few are consumed locally.

A sad reminder of the dangers of fishing occurred in 1965 when Jim Pearson’s brother Benjie was drowned. He was trying to enter the harbour on his own when his boat was turned over by a huge wave.

Agriculture

This remains an important part of the parish economy. John Hunt interviewed two farmers for this summary: Bill McNicol whose family has farmed Castleton Farm (145ha) since 1908, his grandfather buying the farm in 1921 for £11,000, and Andrew Miller whose family has farmed Bonnington Farm (100ha) since 1912, his grandfather buying the farm in 1922 for £7,000. Mr Miller was brought up on a farm near East Linton and took over Bonnington from his uncle in 1967. (See also Environment, where both comment on the changes in wildlife on their farms).

Both farms are predominantly arable though Castleton has a little coastal grassland plus 4ha of woodland. Some additional ground is rented elsewhere (about 30 ha) by both farmers for grazing or cropping.

After the war, mixed farming was practised with a wide variety of crops grown including wheat, barley, potatoes, turnips, sugar beet and hay (silage from the late 1950s). Sheep and cattle were bought in during the autumn and over-wintered, being fed on turnips and hay, with the muck produced then spread on the fields.

Horses were in use on both farms for a period after the war – these were Clydesdales, huge horses used in pairs to pull the plough and for other work. At Bonnington, Mr Miller’s uncle bred Clydesdales preferring them to tractors. Four pairs were used and were only replaced by tractors in the 1950s. At Castleton tractors came in a little earlier but one pair of Clydesdales was still in use in the early 1950s. On this farm there were 18 pairs of horses before the war. One pair of horses could plough one acre a day in good conditions but the early small tractors could manage three acres a day (nowadays much larger tractors plough considerably more).

Until the 1950s all tasks on the farm were labour intensive. Harvesting corn was by binder with the cut crop then formed into stooks to dry before being brought into the stackyard and piled up into large stacks. The corn would later be threshed in a mill – either a static mill on the farm or a travelling threshing mill – in order to produce the grain, which was then put into sacks. Since the late 1950s, combine harvesters have done all this in one operation with the machines getting progressively larger and faster. The grain now goes into an electric and diesel fired grain dryer and large silo before eventually departing for the grain merchant.

Potatoes also demanded a lot of physical work with squads of temporary workers planting, weeding and gathering by hand with the crop stored in outside clamps (layers of straw covered by soil) before being sorted and bagged during the winter. The ‘tattie squads‘ provided a lot of employment up to the late 1960s when potato harvesters came in.

Haymaking was another busy time in the farming year with the cut hay turned by hand until dry and then made into ricks before being brought in on carts and built into a huge stack. Hay was mainly used for feeding livestock in the winter. Haymaking stopped on Castleton in the mid 1950s but continued until later at Bonnington.

Both farms bought cattle each autumn for over-wintering and fattening. At Bonnington, over 100 three-year-old Irish store cattle were purchased at Haddington or East Linton markets – both markets closed in the 1960s. They were kept inside, fed on hay and turnips and sold for slaughter in the summer after fattening outside on grass. Some animals were slaughtered for local consumption at the North Berwick slaughterhouse (where the Safeway supermarket now stands) up to the 1960s when it closed. Recent closures of other local slaughterhouses mean that today animals have to travel big distances to Aberdeen or elsewhere.

Hoggs (young sheep) from Orkney, Caithness or elsewhere in the Highlands were also bought for wintering on the farm – either to be fattened for slaughter or in the case of ewe hoggs for sale on to other farms for breeding. Other livestock on the farm included a few pigs, chickens and a farm cow for milk.

Inevitably, farming changes have had a huge impact on the employment provided. In the 1970s Castleton employed 14 people some of whom were part time, giving the equivalent of about eight full time jobs. They mostly lived in six farm cottages. Other temporary work was provided at peak periods such as harvest time. The number employed just after the war is not known but would have been a little higher than in the 1970s. Nowadays all the work is done on the farm by Mr McNicol with help from his son. No temporary work is provided any longer.

It has been a similar story at Bonnington, which employed four ploughmen up to the 1950s. Their sons also worked on the farm in various capacities as well as the ploughmen’s wives on a part-time basis. All were housed in four farm cottages. Between them about eight full time job equivalents were provided in addition to the farmer’s family. There were also four bothies, three for men and one for women, which provided very basic accommodation for up to some 20 temporary farm workers who helped at peak periods – these were often men from county Mayo or Donegal in Ireland. They fought each other so it was important not to have both at the same time! Today only Mr Miller works the farm with some part time help from his son and son-in-law.

Cropping on both farms is now largely restricted to winter wheat and spring barley (equally split between the two) with some silage also made at Bonnington. About 10% of the land is in set-aside – in grass with no crop produced. Castleton used to over-winter cattle and sheep but this stopped in the 1960s when a large chicken egg rearing enterprise started. That continued until 1997 when it became uneconomic. When the old steading was demolished, the stone which was thought to have come originally from nearby Tantallon Castle, moved on to a third existence in various building developments in North Berwick.

Bonnington continues to over-winter about 100 suckled calves (bought at ten to twelve months of age), which are kept in a huge shed erected in the 1950s to replace the old farm buildings. This shed is large enough to also house a silage pit plus all the straw bales, machinery, fertiliser etc.

The vastly reduced need for labour on the modern farm has been made possible by enormous advances in farm machinery. Each farm has two large tractors (about 90 HP, four-wheel drive), a small tractor for odd jobs and a combine harvester plus a small number of specialised machines such as a forklift truck. Tractors are now very comfortable – fully enclosed, air conditioned and equipped with hi-fi. Simplification of the farming crops has also helped to reduce the number of different tasks required and thus makes it feasible for one highly skilled and well-equipped person to do everything.

Machinery may have displaced jobs but it has eased the physical demands of farming. The ploughmen who toiled behind their Clydesdales were rarely able to continue after the age of 35 because the work was so demanding. If they were lucky they then got lighter work on the farm such as looking after the livestock, but if that was not available they could lose both job and home.

Farming technology has improved enormously and continues to do so. Better varieties of seed, improved chemical weed and disease control plus the use of inorganic fertilisers have resulted in big increases in yield. Two tons per acre of spring barley was exceptional after the war but now three tons per acre is normal. In the 1960s one and a half tons per acre of winter wheat was the norm, now four tons per acre is achieved. With potatoes, ten tons per acre after the war was thought to be phenomenal, now up to 30 tons per acre is expected though irrigation is used today.

Some personal reflections from the two farmers on the huge changes over the period:

The continuing innovation in farming practices and technology has been a challenge and source of satisfaction. Mobile phones, faxes and computers are now a vital part of the job.

Life for farmers has become rather lonely and more stressful, and they miss the many people (including the characters) that used to be around the farm. Visits to the market are now a rare event instead of the frequent business and social occasions of the past.

Since 1996 farming has become less profitable despite the long hours that have to be worked (typically over 70 hours a week at peak periods with holidays a rare event). Farmers believe that government does not care about them and they feel besieged by bureaucracy and paper work.

The future of farming seems very uncertain with the average age of farmers now 58 and a reluctance by the younger generation to take on the long hours, stress and rather solitary life that is involved.

Golf

This has a dual role in the parish – as an important part of the tourist industry, and as an employer. There are two courses – the East course (also known as the Burgh course and originally owned and administered by North Berwick Town Council) and the West links.

In 1950, the East course at North Berwick was played by the Glen Golf Club, Glen Ladies’ Club and the artisan Rhodes Golf Club. The West links was played by the North Berwick Club, Tantallon Golf Club, North Berwick New Club, North Berwick Ladies’ Club and the artisan Bass Rock Golf Club.

Prior to the war, both courses attracted thousands of visitors but during the following decade with so many other distractions, interest in golf declined and the membership of golf clubs fell dramatically. In 1947, the town council held a plebiscite of all the municipal voters to decide whether playing golf on a Sunday should be permitted on the East course. On that occasion the majority voted against, and golf was not played on a Sunday until 11 March 1958.

Part of the West links, (Elcho Green to the March Dyke) is common land, protected by the National Trust for Scotland. The remainder of the West links was purchased by the town council in 1954. Following local government regionalisation in 1975, all the town assets including the East course were administered by East Lothian District Council and the local authority now own the land. Glen Golf Club successfully negotiated a long-term lease for the East course.

By 1962 the membership of the North Berwick Golf Club had declined to a point that the North Berwick New Club was approached to take over their assets including the trophies. On 1 January 1963 the North Berwick New Club adopted the name North Berwick Golf Club and took over the lease of the West links.

Bass Rock Golf Club was the first in the county to offer junior membership in 1961 and by the end of the decade interest in golf had increased, mainly due to the exposure of golf on television. During this period James Watt, the last of the traditional clubmakers retired from his business at the foot of Station Hill. In 1967, North Berwick Golf Club appointed David Huish as its first golf professional, a position he has retained for over 35 years. That year the town council installed electricity to the professional’s shop for the first time. In 1972, the last of the Scottish Boys’ Championships was played over the West links. This event had been played annually at North Berwick since 1935.

Visitors to the area have always been more aware of the town’s golfing heritage and the late 1960s saw an increase in the number of golfers from around the world wishing to experience the West links. The popularity of the course was boosted in 1972 when Arnold Palmer and Tony Jacklin played the famous 15th hole Redan, with legendary golf commentator Henry Longhurst during the filming of an ’18 holes at 18 different courses helicopter round’. The West Links was used as a qualifying course when the Open Championship was played at Muirfield in 1959, 1966, 1972, 1980 and 1992, which added to the profile of the area and the West links became an integral part of the ‘golf package tour’.

In 1978, Tantallon Golf Club celebrated 125 years since its formation, and is now the oldest club in North Berwick. In 1981, the PGA Senior’s Championship was played over the West links, which was won by Australian Peter Thomson. That year the dry spring weather left the course burnt golden brown, and the competitors described the links ‘like playing golf on the Sahara desert’. Ten years later an automatic watering system was installed and since then the rainfall in this district has been the highest on record.

Despite the new golf equipment, the East course and West links continue to be a formidable challenge. The golf clubs have a full membership, some with a seven-year waiting list. The courses continue to attract prestigious tournaments including the Vagliano Trophy played over the West links, and the British Blind Society that held its International Match over the East course in 1997.