Tourism | Railway | Crafts | Fishing | Agriculture | Forestry | Golf

Longniddry people worked in a wide range of occupations in the years between the second world war and the rapid expansion of the village around 1970. The owner-occupied part of Longniddry was inhabited almost exclusively by business and professional people. In ‘the Village’ there were tradesmen, manual workers, and a scattering of clerical and professional people.

Immediately after the war there were quite a number of civilian employees at the army base in Gosford Estate. Several of them were allocated council houses in Wemyss Road, and most of them left when Gosford Camp was closed down. Quite a few Longniddry men in the 1950s and 1960s were also employed at Calum Grant’s (later Lothian Structural Developments), a galvanising plant near Gladsmuir, which closed in the 1970s.

However, the importance of Longniddry as a busy railway junction ensured that a significant number of men in the village were railway workers. Also, Longniddry was surrounded by farmland, and indeed until around 1970 several of the community’s streets were separated from each other by cultivated fields. Agriculture was still a fairly labour-intensive operation, and employed a number of village residents, and of course everyone who lived on the farms round about. There were no computer programmers living in renovated farm cottages in 1950! Even the majority of villagers who had no connection with farming could not but be aware of the work of the farming year as it unfolded around them and in their midst.

Thus, the two sources of employment that convey the essence of Longniddry in the period 1945-65, were above all, agriculture and the railway.

Several Longniddry people were at one time employed by Gosford Estate in various capacities, but the estate now employs very few, if any, Longniddry people. There are no other significant employers in the Longniddry area. The overwhelming majority of Longniddry people work outwith the village and its immediate area. Since most Longniddry people are in ‘white collar’ jobs of some description, Edinburgh has a crucial role to play. Indeed, the very reason for Longniddry’s expansion is its proximity and easy access to Edinburgh. The village’s setting may be rural, and its history long, but its future lies as a dormitory suburb of Edinburgh.

Tourism

The seaside car parks are very popular with day-trippers. Apart from that, Longniddry could not be said to be a tourist destination, and there is next to nothing in the village in the way of tourist accommodation. It is perhaps strange that, in spite of its excellent beach and golf course, and easy access to Edinburgh, Longniddry has made no attempt to attract tourists, but this is indeed the case. In recent years three or four private houses have begun to offer bed and breakfast accommodation, but there are no hotels, guest houses, or camp sites. The Longniddry Inn is something of a misnomer, as it has no bedrooms and cannot provide overnight accommodation. A proposal for a golf course and hotel at Seton Mains, to the west of the village, was recently turned down by East Lothian Council.

Industry

The railway

Nowadays, at the beginning of the 21st century, Longniddry is an unmanned station. Not a single employee works there, and the two bare platforms are graced only by three graffiti-bedaubed basic shelters. However, things were very different in the 1940s and early 1950s. Longniddry was a busy railway junction with goods trains running on one branch line to Aberlady and Gullane, and on another to Haddington. Until 1949 there was also a passenger service to Haddington. At Longniddry station there was a ticket office, waiting rooms, bookstall, a towering three-storey signal box, and a large goods yard.

The way the old station was set, there was four houses over – the Station Cottages – then when you came into the goods yard the first building you came to was Tom Dickson’s who was the signal engineer, telegraph and signal engineer. The next one was Owen Traynor’s, he was the stores manager, and then the next one was the surfaceman’s, and the next one was the lamp room for the paraffin for the lamp room, and then down to the station.

Bob Porteous

The numbers of men employed at the station in the late 1940s are surprising to say the least. Almost all of them lived locally. The station was manned by two shifts.

- Booking Office 1st shift Greta Grierson

- 2nd shift Andrew Scott

- Foreman porter 1st shift Donald Hutcheson

- 2nd shift Charlie Bruce

- Porter 1st shift Jimmy Glen

- 2nd shift Bob Melrose

- Three shifts were worked in the signal box 1 John Aitchieson

- 2 Charlie McNeill

- 3 Harry Reid

- Relief signalman John Grierson

- Signalman/Telegraphic engineer Tom Dickson

- Signal fitter Willie Small

- Storeman Owen Traynor

- Station Master Willie Kerr

- Ganger Hugh Reynolds

- Surfacemen Archie Porteous, Wull Henry, Bob Samuel, Eck Wilson (Known as ‘Stabs’ Wilson because of the amount of fencing he did), Jimmie Ramsey, Jimmie Lugton, ‘Auld Telfer’.

- Engine shed Willie Griffin, driver

- Willie Nicholson, driver

- Night watchman ‘Auld Cruikshanks’

- Bookstall Mr McAdam

- Porter/signalman Archie Samuel (His work in the Aberlady Junction signal box at the Spittal was only part time. The rest of his day was put in helping around the station.)

(Source – Morris Glen)

The station was always a magnet for boys, who were encouraged by some railway staff who enjoyed their company.

I used to run away from the school when it closed in the afternoon (c1937) and I used to get on the engine and go to Haddington. The driver was old Charlie Cruikshank … the fireman was Willie Nicholson … and we used to go to Haddington. They had a special box for me to stand on to drive the engine.

Bob Porteous

It was easy for young boys with an interest in railways to get a start in some lowly capacity after leaving school, such as

… repair book attendant, it was a job that entailed, when the driver came into the shed, he handed in a line with all the repairs, and I wrote them into this book, and they were allocated to the different fitters.

Bob Porteous

My father says to me, “You’re no very keen on that job wi … that plumbin job”. I says, “No, I’d rather be on the railway. He says, “Well, there’s a job coming up at Prestonpans. If you like, I’ll phone the station master at Prestonpans.” And the station master at Prestonpans at that time was Harry Graham. My father phoned him and Harry Graham came along to the house to see me. He came into the house this night and he introduced himself as Harry Graham, and he says, “I’m the Station Master at Prestonpans. Your dad tells me you’re looking for another job, son; ye’re no happy in the plumbin.” I said, “No, I don”t really want to be in the building trade. I want to be in the railways if possible.” And he says, “Right I’ll start you at Prestonpans.” And he had the authority in these days (c1947) to start you. And all that happened was I went up to Waterloo Place, that’s where headquarters were then, and I got a medical. And I started at Prestonpans station as a Number Taker, going round all the collieries … And every wagon that was in the collieries, whether it be for loading or unloading or whatever, I took the number and gave the details to the clerk at Prestonpans.

Morris Glen

Once a boy had started on the railway, unless he was hopelessly ncompetent or did something spectacularly foolish, he had a job for life. After a year or two he would be encouraged to choose the particular area of railway work that interested him and in which he wished to make his career.

Many chose to become the ultimate small boy’s role model, the engine-driver. It was not necessarily an easy ambition to fulfil, however.

I was on that job for a year until I was age to go on to the cleaning. Then I started cleaning engines. But during the war I only cleaned one, because promotion was so quick I went on to … fireman. You had to be so long a fireman, and then you passed as a fireman, and then so long and you passed as a driver … I was a long time a fireman. I was a fireman from 1941 to 1960 … I cycled to Edinburgh for 19 years.

Bob Porteous

Others might move into signalling, which usually involved starting as a temporary signalman, then applying for every vacancy that came up until a permanent position gave you a foothold on the ladder. In 1953 the lucky young man who landed a signalman’s job earned £5-17-6 a week, and for night shift ‘close on £8’ (Morris Glen) which was not a bad wage, if compared, for example, with agricultural wages.

Every encouragement and assistance was given to young men keen to get on, who wished to further their career and education. The upper echelons of railway administration, in its days as a nationalised industry, were staffed by men who had risen from the ranks, not by business graduates or professional managers parachuted in from elsewhere.

I remember going to the area manager’s office in Edinburgh years and years ago, and he wasn’t in. And I was waiting to speak to him, and I saw his seat there, you know, this leather seat behind the desk, And I said to myself, ” I’ll sit in that seat some o’ thae days.” And I sat in that seat!

Morris Glen

To return to the Longniddry Station of the 1940s and 1950s; the station was a hive of activity:

We had a lorry at Longniddry that delivered Longniddry, Aberlady, and Gullane … There was two loading banks and one other road where you could load putting the lorries right up to the wagon.

Bob Porteous

The variety of goods transported in and out of the station is fascinating;

They had a train at night that started from Dunbar they called the ‘Drem and High Street’ – vegetables to be on the market in Glasgow the next morning. And it went Dunbar, Drem, Longniddry, Prestonpans, and then that was it…. All the cabbage plants came by train … and the farmer came and collected his cabbage plants.

Bob Porteous

They loaded tatties and everything at Longniddry … sugar beet.

Albert Ogg

Crates of dead rabbits came down from Haddington, and baskets of racing pigeons were off-loaded at Longniddry to be released from the station platform. There would be fowls in boxes, calves in bags, grain and cattle to load or unload.

They used to put calves, a young calf, in a sack, and tie the neck round the neck of the calf. The poor calf couldn’t walk. It just, when it was put down, that was it till it arrived at its destination.

Bob Porteous

Perhaps strangest of all

They used to send away bag-loads of crows to make crow pie. They went to England.

Bob Porteous

The Haddington branch line carried a passenger service until 1949, and a goods service until 1968. The engine was based at Longniddry, and after the last passenger train arrived in Haddington in the evening, the engine returned without the coaches to Longniddry. Early next morning it would pull a goods train to Haddington, then bring down the first passenger train of the day. The engine returning from Haddington at night was often crowded with youths returning from dances or the pictures – ‘as many as you could get in.’ (Albert Ogg) – a blatantly illegal practice which was nevertheless taken for granted.

Ye mind old Mr Welsh the chemist? (Willie Griffin was the driver I fired tae.) His young family were all born in the Vert in Haddington, and Welsh, he used to get down on the engine when he was visiting his wife … anyway, he was aye on the engine.

Albert Ogg

As for working on the Haddington line,

…that was in 1945, and I was only a year on the Haddington branch, David, and I went into the air force … We started at 4.40 all week, like, ye ken. But on the Monday morning we turned out two ‘oors earlier to light the engine fire … the fireman got a couple of hours overtime tae dae it … And ye got oot and ye met the goods from Edinburgh in the morning, 4.40 in the morning … and ye left for Haddington wi the goods …quite a busy branch wi the goods traffic, you know, Haddington … coal, various things, cattle … Anyway, at Haddington ye shunted them off, and when ye were feenished ye cam doon wi the train, first passenger.

Then ye did that till ye got a connection wi the Berwick slow in the mornin aboot twenty minutes to nine. Ye met it, and efter that ye went and put some more coal on, coaled it up, you know … and shunted all the traffic (ie wagons) that was left on the North Berwick goods. And ye had Aberlady and Gullane – ye went doon the Gullane branch. We did Aberlady and Gullane and came back up. And then ye started again wi the passenger, was it eleven o’clock? … Ye came doon at denner time and got relieved at Longniddry station by the back shift.

Albert Ogg

The present generation’s experience of railway porters may well be limited to period television dramas, where porters seem to be solely engaged in tipping their caps and dutifully carrying ladies’ luggage on and off trains. However, in the real world things were not so easy.

The carts were coming one after the other with potatoes. And you had to load the wagons almost to the roof. You had grain to load, and you had 16 stone bags of grain to load on to wagons … They went home tired, believe you me! And then there was a great deal of parcel traffic. I mean, Longniddry at that time … the lorry I’m speaking about from Gullane, he had all of Longniddry to deliver, all the parcels. There was no vans came from Edinburgh; all the traffic came by train.

Bob Porteous

Porters also had to wash out cattle wagons, and there were

…taps to clean, waiting rooms to clean, toilets to clean, windows to wash’. As for carrying passengers’ bags, ‘That was his easy work!

Bob Porteous

The derailment of 17 December 1953 made a lasting impression on Longniddry’s railwaymen. The train in question

…was a relief train that they had put on with Christmas parcels for the south … So when we came into the village, there was a policeman standing at the Bank, and he had his hand up, and he turned the bus into Links Road … So I jumped up and I says to the conductor, “Just let me off here” I says “What’s the diversion for” He says, “There’s a rail smash up there”… So I jumped off the bus at the co-operative and walked down through the village, and I couldn’t believe the mess that I could see as I was walking through the village.

Morris Glen

There was a set of miniature rails on a wagon. And instead of being tied by chains they were tied by rope. And due to the oscillation of the wagon the rope became severed and the rails parted company with the wagon, and wedged on the opposite line and derailed the train coming the other way. Unfortunately the ramp of the platform was where it was derailed, and the train mounted the platform, and it actually turned in the opposite direction within 90 yards of the way it was going. It was facing back to Edinburgh, and the tender was about 40 yards from it. The fireman was killed. The driver was still in the engine when it was down the banking. The driver fell about eight feet and broke his leg and that was all that was wrong. Unfortunately the fireman didn’t be so lucky. He was in pieces. In pieces! … I was in digs with Miss Wight when the station master, Kerr, came round knocking at the windows, “Come on, come on! There’s been a disaster!”

Bob Porteous

Since the train was made up of mail coaches, and not wagons, it apparently caused the station master to believe at first that it was a passenger train.

The whole train went forward and scattered all over the place. It was nothing but a bloody mess! The line was torn up, rails sticking up in the air. Just like matchsticks, sticking up in the air!

Morris Glen

Meanwhile several near neighbours slept on oblivious:

My best man, he was in the house 20 yards from it and never heard it

Bob Porteous

Well, look where I stayed. 5 Wemyss Terrace. And the wife said I got up in my bed went back to sleep. Kerr didnae come and waken me anyway!

Albert Ogg

The hero of the hour was the young lady doctor Isobel Jarvis, who treated the driver and crawled under the wreckage to help to bring out the fireman’s body. The dead man was

… Donald McKenzie. The driver was Davie Drummond. I knew the fireman.

Albert Ogg

Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, the Haddington line is a railway walk, and the Aberlady and Gullane branch has disappeared over most of its length. The station buildings have vanished without trace, the platforms have shifted some 50 yards or so eastwards, the goods yard has become a car park, and Longniddry station now gives employment to nobody whatsoever.

Crafts

During the 1970s, a wood turner operated from a workshop in the Kiln Cottages. When the buildings were renovated as dwelling houses he left the village. Around the same time a young couple made dolls’ houses and model buildings in a workshop in the old Garden City Hall; they too eventually moved on. A local woman, now resident in Haddington, has a workshop and kiln near the old limeworks outbuildings, where she produces stained glass.

Fishing

As Longniddry expanded, several Port Seton fishermen bought houses in Longniddry. At least one boat has been seen in Eyemouth harbour with the home port ‘Longniddry’ painted on the stern! However, there are of course neither harbour facilities at Longniddry, nor any tradition of fishing.

Agriculture

All the building expansion until the mid 1960s took place on land that had been part of Longniddry Farm. David Robertson talked with tenant Gordon Morrison:

That’s some of the best land in East Lothian that’s been built over.

Mr Morrison is a tenant of Wemyss & March Estates, and has farmed Longniddry Farm since he inherited it from his father in 1948. Much of the large original early 20th century farm of 700 acres has been swallowed up by the expansion of Longniddry, but to compensate for this other fields are rented in Gosford policies and at Craigielaw, near Aberlady. He now concentrates exclusively on growing wheat, barley and oilseed rape, and on breeding and raising beef cattle. Crops formerly grown on the farm included potatoes, oats, swedes, mangolds, and sugar beet. Around 1950, the farm employed eight or nine men, several women, and squads of seasonal workers. Every farm cottage on the farm housed a farm worker and his family. Now Mr Morrison employs only one man, who does not live on the farm.

In 1950, horses still pulled the plough, and most of the grain harvest was cut by the binder, stooked, stacked, and subsequently threshed. Nowadays Mr Morrison breeds cattle and grows only wheat, barley, and oilseed rape. In 1950 hay, swedes, mangolds, sugar beet, oats, and potatoes were also grown.

In the post-war years the labour force on Longniddry Farm was ‘eight or nine men, and three or four women’. There were ‘four pairs of horses and an odd horse. And then mares breeding as well’

Tam McDonald in his garden in Amisfield Place, 1940s. The field behind the garden contains stooks of corn, and the large villas of Gosford Road can be seen in the distance. These fields have all been built over (A&J Gordon)

The ploughman’s day went as follows,

The horses were fed at six in the morning and they started roughly half past seven, and then stop at quarter past eleven in these days, and lunch till one – that’s to give the horses more rest! Ha ha! And then from one till five. And quarter past eleven on a Saturday.

Women did such jobs as hoeing and singling turnips and sugar beet, and forking sheaves at harvest and threshing. ‘They did everything. They worked like men’.

Extra labour was hired for the potato lifting, local squads from Haddington or Dalkeith, or Irish squads whose macho amusements could sometimes seem a little extreme to the douce East Lothian farming community.

They used to go up into the stackyard and just knock the stuffing out of each other for fun … I’ve seen the men carrying 15/16 stone bags of grain round the back there, and one of the women used to sit on the top of it … They were mad of course.

In 1950 Mr Morrison’s ploughmen earned (in modern money) around £1.50 to £1.60 a week. They had a free house, 16 bags of potatoes a year, and free milk from the farmer’s cow when it was available.

The local farms kept the village blacksmith in business, not just for the shoeing of horses, but in the maintenance and repair of implements.

Anything worn on machinery he would lay it, as we would say. Take the coulters down and he would lay them – reshape them. All the plough machinery got worn. Nowadays of course you would just buy new ones. It costs a fortune. You used to always take them down and get them laid.

Several of the farms in the area specialised in vegetable growing until recently. Now, as at Longniddry Farm, agriculture is given over almost entirely to barley, wheat and oilseed rape.

George Mitchell, of Chesterhall and Archerfield, specialised in vegetable growing. Most of the fields between Links Road and the Dean were his, and several of his employees were given new council houses in Wemyss Road in the early 1950s. Apart from the actual ploughing and driving, most of the work in vegetable growing was considered women’s work, and squads of women could be seen labouring in Mitchell’s Fields at all seasons of the year. Not many of them were Longniddry women however. Field work was not popular among the women of the village most of whom by the 1950s considered themselves rather too good for such lowly toil.

My informant, who wishes to remain anonymous, worked for Mitchell as a young woman, met her husband there, and went back to work after her children went to school in the late 1940s and 1950s.

You used to walk down and cut the cauliflowers. And what else? Cabbage, cauliflower, leeks – dig leeks, and sometimes the ground was so hard with the frost it could be a terrible job, that. It was hard work but we survived … What else? Well in the summer time it was lettuce, sybies; but it was mainly lettuce. He sold an awfy lettuce. Hoeing and weeding. Singling. Beetroot, he grew beetroot … Weeding, on your knees, crawling along the ground all day.

The women got their orders from a grieve;

We started at seven. When there was orders, big orders, we used to go out at four o’clock in the morning.

Overtime was paid for such early starts but the squad worked on till 5pm irrespective of the starting time. Mrs Anon remembers working in near darkness on Christmas Eve to finish a big order, pulling Brussels sprouts with the snow lying on top of the plants.

I can’t remember when Christmas Day became a holiday, for at one time you always worked. You got the New Year’s Day off, but you didnae get Christmas.’.

The farm grieve’s diary makes it plain that it was also business as usual at Christmas on Longniddry farm in 1950.

The women got an hour for lunch, and took a ‘piece’ to eat. There were short breaks morning and afternoon. As for toilet facilities,

That was a bother. That was a bother! No, there were just woods! You were lucky if you got to a toilet.

Many of the women wore the distinctive ‘uglies’

It was a bonnet. And it had canes so that you could pull it right out. And there was a wee bit at the back for your neck. To keep the sun off you, or the weather.

It may seem fantastic to compare East Lothian with America’s Deep South, but as far as working conditions went, my informant was of the opinion that ‘It was like the black people. It was the very same.’

Mitchell’s Fields, of course, are now just a memory. This rich market gardening land was all built over between 1965-75.

It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Longniddry Farm may go the same way in the not too distant future. Quite apart from the severe crises which have rocked agriculture in recent years, there is a feeling that the big building firms have not entirely given up hope of exploiting Longniddry’s fertile acres, and that the council might not be entirely unsympathetic to their ambitions.

Well, I’m quite glad that I’m getting to the finish of farming really. I don’t know what’s going to be in the future, because there’s still talk of building a new town here. That’s still being talked about.

Gordon Morrison

As well as Longniddry Farm, there were a number of smallholdings and market gardens – almost all gone now. One of the schemes associated with the Garden City war veterans’ homes was a sort of agricultural co-operative around the former limeworks; when the scheme was eventually wound up, the ground was rented out as a smallholding, and continued as such into the 1970s. The fields were taken in by Longniddry Farm and the outbuildings allowed to become ruinous.

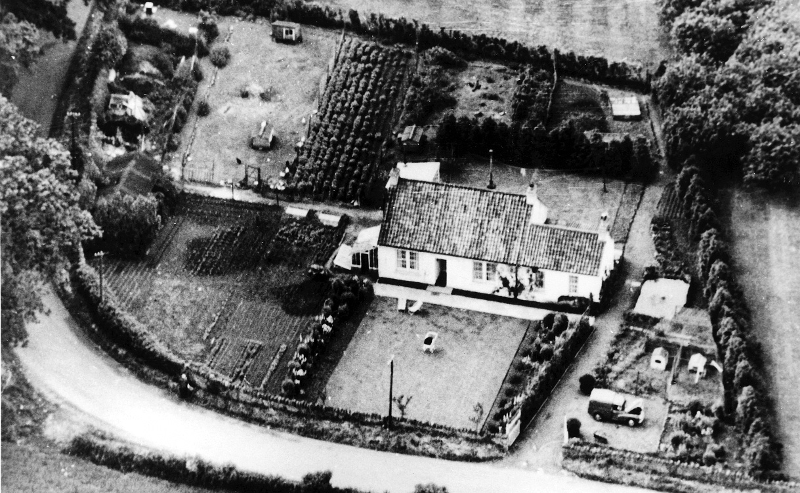

Ben Mackintosh’s smallholding at the Dean c1950; the house still stands, much extended, but the adjacent ground has all been built over (A&J Gordon)

Another smallholding at the Dean was cultivated well into the 1960s. The house still stands, much extended, and the land has been built over. In the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, there was a market garden in Elcho Road; this, too, was built over in the 1970s. There is a market garden at Redhouse, a mile-and-a-half to the east of the village. The present proprietor now specialises in garden plants and cut flowers. There was an extensive orchard and market garden at Longniddry Gardens, adjacent to Longniddry House, where the present writer and many of his contemporaries spent many happy days in the early 1960s picking gooseberries, hoeing, and cutting lettuce and cauliflower. The proprietor never discovered the identity of the ruffian who crashed the new tractor into a plum tree. The ground was built over c1970, but many of the fruit trees still remain.

PHOTO 14 Ben Mackintosh’s smallholding at the Dean c. 1950; the house still stands, much extended, but the adjacent ground has all been built over.

PHOTO 15 Tam McDonald in his garden in Amisfield Place in the 1940s. The field behind the garden contains stooks of corn, and the large villas of Gosford Road can be seen in the distance. These fields have all been built over.

A more rural Longniddry

PHOTO 16 Chirnside’s smiddy in Longniddry Main Street in the early 1950s. The smiddy is now part of the Longniddry Inn.

PHOTO 17 Longniddry Golf Course in the 1950s with a flock of resident sheep. The tank traps in the foreground were supposed to hinder German invasion in the second world war. They have now almost all been removed.

Forestry

Gosford Estate, bordering on Longniddry, is well wooded, although commercial exploitation of the timber has been minimal. Maintenance of the woodlands over much of the period 1945-2000 was fairly haphazard, but has improved greatly in recent years.

A sawmill operated in the former army camp premises in Gosford policies (in Aberlady parish) a mile or so from Longniddry from around the 1970s until 2000. Owned by a local businessman, this firm harvested and processed timber from all over Scotland. It also undertook the maintenance of the Gosford woodlands. The business has recently downsized radically, and now deals mainly in fencing garden huts, and garden furniture.

Golf

Golf plays an important role in the economy of Longniddry. In the 1920s, the 18-hole Longniddry course took in land on both sides of the coast road. During the second world war, much of the course was ploughed up for agriculture, but was returned to the golf club at the end of hostilities. The course was reopened in 1947, now lying entirely south of the coast road.

In 1996, the year of the club’s 75th anniversary, there were 1122 members. The club employed a head greenkeeper, an assistant head greenkeeper, and four other greens staff. There was a resident clubmaster (club steward), and kitchen, bar, and cleaning staff. There was also a golf professional with two young assistants.

Other communities in East Lothian have hotels and other businesses that successfully exploit the county’s reputation as a golfers’ paradise. This is not the case in Longniddry, and it is rather strange that so far there has been no attempt to exploit the business potential of attracting parties of golfers to the village.

Wemyss & March Estates have just completed a new golf course at Craigielaw adjoining Aberlady village. The estate also has planning permission for another golf course in Gosford policies, coming close to Longniddry. East Lothian Council recently turned down a planning application for a golf course at Seton Mains to the west of Longniddry. Landowners now see golf courses as an attractive alternative to agriculture, especially if the courses can be constructed in conjunction with lucrative executive housing developments. This is a prospect that is not going to disappear from the Longniddry area. The demand for building land in Edinburgh’s commuter belt seems insatiable, and one suspects that planning authorities may not be able to resist the pressure for ever. At least turning the land over to golf would stop the open countryside around Longniddry being completely swamped by a tide of housing.