Tourism | Industry | Agriculture

Tourism

Being neither a coastal town nor a centre of golf, Haddington was not, for many years, promoted as a tourist attraction. Nonetheless, its beautifully preserved townscape and role as county town attracts many of the county’s visitors. However, by 2000, it is increasingly recognised that tourism comes in many forms, and that Haddington is perhaps not promoting itself as well as it might. It is also worth considering that, had the town been in the limelight in earlier years, then much of what makes it attractive in 2000, may well have been destroyed in pursuit of modernisation.

Industry

William Dods | Sinclair McGill | Richard Baillie | Bermaline | Thomas Bernard | Burns Coulston | Gateside | Mitsubishi | Gas Company | Kilspindie | Macnab | Alexander Paterson | George Patterson | Poldrate Mill | Ranco | Robertson Brothers | Stewart & Buglass | TD Precision Engineering | Courier | Recollections

The oldest industry in Haddington, which is still in business, is William Dods and Son/Dods of Haddington. William Dods, a smallholder in the Letham area, was so successful in saving his cabbage seed for use the following year that others wanted to buy seed from him. This led to the foundation, in 1782, of the firm of William Dods & Son, seedsmen, in Haddington. In 1945, the business was at 26, 28 and 30 Court Street, with warehouses behind. The main trade was in grass seed, sold all over Scotland, but in 1962, in response to the increasing demand for cereal seed, a new cleaning plant was installed, followed by bulk rather than bagged intake of grain, and then automatic bag stitching and weighing. In 1970 a new shed was built behind the warehouse, and seed was also stored on four outside sites.

1972 saw the purchase of a site on Ugston Farm, west of Haddington, where a large storage shed was constructed, with a further shed and new seed cleaning plant being added in 1975. The site was named Backburn, after the burn behind nearby Letham House. The Court Street premises were sold to Laws of Newcastle for a supermarket, and the Dods office moved to St Anne’s Place. The 1970s brought forklift trucks and pallets, a dedicated seed testing laboratory, and a grain drier. An office was built at Backburn.

The bi-centenary was celebrated in 1982 with a party for 500 guests, and this decade also saw the first computer system installed (1983), more grain storage bins (1985), and an enlarged grain cleaning line (1986). The drier caught fire, and was replaced. The computer system was upgraded in 1992, and 1998 saw the arrival of an automatic palletizing line.

In 2000 the company is staffed very much as it was in 1945 – with four directors, two clerical and three warehouse staff, and an outside selling staff of seven. The big difference is that the throughput was up more than tenfold in this period.

Another firm in the seed business, founded even earlier, in 1755, but no longer existing, was Roughead & Park/Sinclair McGill. This firm supplied to farmers and market gardeners a wide range of seed stock suitable to Scottish soil and climatic conditions, imported from around the world. In seed lofts between Court Street and Lodge Street the seed was cleaned, graded, then expertly mixed, packaged and labelled for distribution. Initially seed bags were woven and sewn by the company’s warehouse staff in Haddington. At peak times about 20 people were employed.

The firm remained independent until 1957 when an amalgamation with the Ayrshire company, Sinclair McGill, took place. This led to the acquisition of additional warehousing in Sidegate, but after restructuring in 1971 the company became Sinclair McGill Seeds. In 1978 the grain store moved to Ayr; the Lodge Street premises were vacated in 1979, and the Sidegate premises closed in 1986. The seed lofts in Lodge Street were purchased by East Lothian District Council and used for some years as library headquarters, while the Sidegate site was later developed for housing, and renamed Brewery Court.

Other industrial undertakings in existence during the period 1945-2000 included:

The abattoir which was built in Gifford Road in 1901, local butchers and farmers used this facility prior to its closure in 1962. Intestines from healthy animals were collected by a local man and processed in his premises in Tyne Court. The treated skins were sold to local butchers who used them to manufacture sausages in various forms.

Richard Baillie & Sons, Public Works Contractors; Richard Baillie founded his business at Pencaitland in 1902. A skilled and hard-working stonemason with business acumen, he progressed to taking on major public works; for example, in 1928 he bought Amisfield House, demolished it, and used some of the stone to construct the Vert Memorial Hospital, Haddington. One contract was to construct the Lady Bower Dam in Derbyshire during world war two, then the largest public works contract awarded to a Scottish company. Delays were caused by the RAF Dambusters Squadron practising in the area, but when the dam was completed it was opened by King George VI. Richard Baillie was also a talented untaught painter. After his death his four sons continued to run the business, but the company went into receivership in 1962, with the loss of over 300 jobs.

Bermaline/Pure Malt Products Ltd operates from the Bermaline Mill, on the river Tyne just east of the Victoria Bridge, occupies a site which had been in industrial use for some 800 years. Bermaline had produced flour for use in the baking industry since the 19th century – the Bermaline Loaf was famous. In 1972 the shares in the company were acquired by the Turner family, and it has been run from then as a private limited company. Prior to the sale there were about 20 employees; now they number 60. The emphasis changed to supplying malt products for the distilling and brewing industries. There were cutbacks in the 1980s due to reduced demand, but a wide range of products is made – the emphasis being on malt bought mainly through merchants, but some direct from farmers in East Lothian. The change of name was made in 1986.

Thomas Bernard & Sons/Simpsons; Thomas Bernard & Sons of Leith purchased a distillery on the Tyne at Haddington near the West Mill in 1835, and continued malting and distilling at this site. A high percentage of the barley was supplied by local farms, and to keep up with demand they bought two other buildings in Haddington. The company also owned housing for many of their employees, but it was subject to flooding, and after the severe floods in 1948 they had to be rehoused elsewhere in the town. The maltings continued to prosper and to expand at the main site, and in 1963 invested in the most up-to-date automatic malting process in Europe, resulting in higher production per man. In 1972 Thomas Bernard & Sons merged with Simpsons, a Northumberland-based malting company. Further development was planned, expected to cost £10m over 10 years, but the planning authorities made conditions which the company was not prepared to accept, and production was gradually scaled down, eventually coming to an end in 1992.

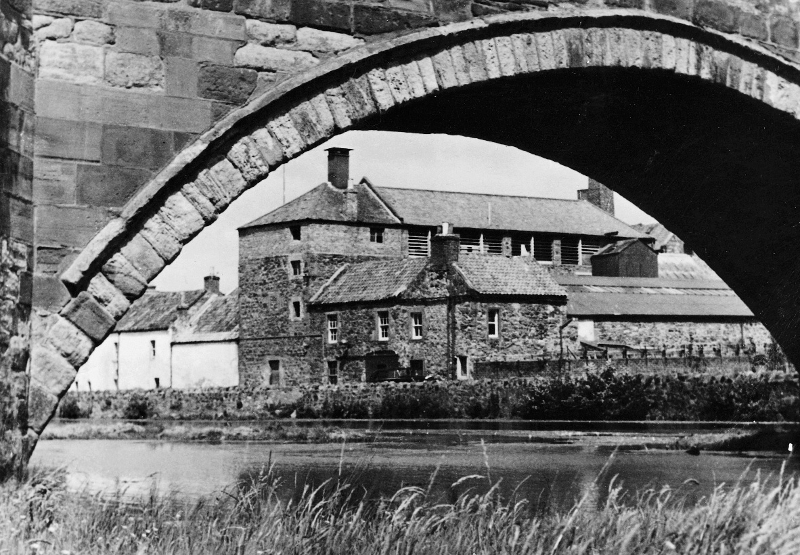

Tannery, Nungate, from south west, c1955

Burns Coulston Ltd, a tannery and wool merchants’ business in the Nungate, suffered extensive damage by fire in 1969. No one was hurt, but 25 people lost their employment as the company decided not to re-build. Pelts had been collected from Lothian slaughterhouses, and the best quality skins were used in bagpipe manufacture. The site was purchased by East Lothian District Council Housing Department, and the residents of Tyne Court can claim some of the best views on the Tyne.

Gateside Industrial Estate: once a dairy farm, Gateside was purchased for industrial development, and the planning committee of East Lothian County Council in Haddington worked hard to provide finance to construct premises for involvement in the growing electronics industry. In 1969 a modern factory was built, and the first tenants were Hilger Electronics, with a highly skilled workforce of 50. The company’s products included instruments for Blackford Observatory and Herstmonceux Castle, and sub-contract work for Plessey. Work was also done for Coradi AG in Switzerland, and when Faul Coradi joined the board, the name was changed to Faul Coradi. Because of the loss of a major contract in California the Chicago Rope Co withdrew their financial support, and the company was forced into receivership. A few of the staff moved to smaller premises at Macmerry, trading as Whitwell Data Systems.

Next to come to the factory was Tandberg, a Norwegian television manufacturer, which wished to open its first factory outside Norway to benefit from closer contact with British university departments in the field of electronics. The factory opened in early 1975 with 50 suitably skilled staff to produce colour television sets, with planning to expand to 150 employees in 1976 and a target to produce 20,000 TV sets per annum. Trading conditions became difficult for the parent company in Norway, but funding of £2m was found to expand and improve the Gateside factory, 50% of the money being raised from public funds in Scotland. Despite a healthy trading balance, and a determined exercise to have the Haddington factory go independent by a management buy-out, the Tandberg factory was put up for sale by the receivers in January 1979, making 120 skilled electronic employees redundant.

Mitsubishi Electronic followed Tandberg in 1980, the trained workforce and factory building ideal for their expansion plans in producing TV sets. Output grew to 2000 sets a week, mainly marketed in Europe, and employing 500 staff at peak times. For 20 years the factory prospered, until in 1999 the corporation reviewed their business operations worldwide, and moved the TV production to Turkey and Mexico, closing the Gateside factory with the loss of 500 jobs.

Converted into smaller units, with the new title of Gateside Commerce Park, the building now houses Scotprint, a company producing state-of-the-art computer graphic colour printing, which employs 120. Another unit is occupied by Hunter & Foulis Ltd, a firm of bookbinders that relocated from Edinburgh, and which employs 90 workers.

The Haddington Gas Company at Rosehall ceased to manufacture gas in 1962, when Haddington was connected to the national grid system (Scottish Gas), making twelve employees redundant. There continued to be an office and showroom in Hardgate for a number of years.

Kilspindie Knitwear was founded in 1917, with premises in Market Street, and a mainly female workforce. The Kilspindie label was to be found in top fashion houses, and its products were sold worldwide. Increased demand led to expansion of the premises, and further expansion was undertaken in 1950-65. The workforce was increased to 325, and it was found necessary to bus workers from Edinburgh. A number of ladies had knitting machines installed in their homes, working on a piecework basis. Production at this time required the post office to provide two collections of parcels per day, and sometimes four vans were needed. Trading in the mid 1970s became difficult due to 20% inflation and a worldwide recession. There was a gradual reduction in the workforce, but the company was saved by a take-over by an Irish group with the necessary funds to install more sophisticated machines. Eventually Kilspindie was taken over again by an English group, which proceeded to run down the business by transferring work and jobs south. Kilspindie was put into receivership and all remaining employees dismissed in 1991.

A small number of skilled workers from Kilspindie continued to produce knitwear from a section of the defunct West Mill (Kerr-Knit), supplying the top end of the fashion trade. The Kilspindie label can still be found in fashion shops, sourced from where is not known.

Adam Paterson & Sons Ltd/A. & J Macnab Ltd: the West Mill site by the Tyne had been used since the 16th century for milling and tweed manufacturing powered by the river. There had been many different businesses before Adam Paterson, a woollen manufacturer from Stow, took over the tenancy in 1885 for spinning and weaving. A limited company was formed in 1906 under the joint management of the Paterson and Blake families, with the new firm known as Adam Paterson & Sons. The firm prospered, producing high quality tweeds for the top end of the fashion industry with clients worldwide. The Queen, in 1956, had a coat made in West Mill boucle tweed, and awards were received against international competition. In 1964 the West Mill changed hands; it was bought by A. & J. Macnab, an Edinburgh based company. Despite several severe floodings and fires the firm continued to function, greatly helped by the good relations that existed with work force and management, and in 1965 there was a workforce of more than 190. Three provosts of Haddington held posts of responsibility in the mill. Additional looms and ancillary equipment were added to increase the range of products for export, but trading became difficult in the late 1970s, and the parent company decided to reduce the work force in Haddington, the mill eventually closing in 1984.

A small number of weavers continued to produce tweeds and tartans for direct sale to the tourist trade.

Alexander Paterson & Sons: the Peffers Place Saw Mill was established in 1875, employing ten men. The enterprise supplied a wide range of home and foreign timber, including pit props, most of which were dispatched by rail from Haddington station. Paterson’s horse-drawn lorry delivering logs was at one time a familiar sight about the town.

After the sudden death of Bobby Paterson in 1975, his widow continued the business for several years, but eventually it was taken over by an English company, which moved operations to Perthshire.

George Patterson & Sons: George Patterson started as a carter with one horse-drawn vehicle in the early 1900s, taking produce to Edinburgh, and returning with supplies for Haddington traders. The business soon expanded, and by 1945 was using more than 30 motor lorries. When Mr Patterson retired in 1950 the business was taken into the British Road Service group, with James Guy from Aberlady as manager. A new garage was built in Mill Wynd, but in 1973 BRS moved their depot to Portobello, and 82 men were made redundant.

A new company was then established from a site on the old Haddington railway station yard, trading as Findlay Guy Transport.

Poldrate Mill: Haddington was once the centre of the grain industry in Scotland, the Tyne providing the necessary power for milling. A mill at the Poldrate had been in operation since medieval times. The last proprietors, W.B. Morrison & Co, produced poultry and animal feeding for local farmers until the business closed in 1967. The buildings were converted by the Lamp of Lothian Trust to provide a home for arts and crafts.

Ranco/LEMAC/Jakes: Ranco Controls, an American company that had set up its first Scottish branch at Uddingston, opened a Haddington unit in 1956 at St Martin’s Gate, employing ten people. This unit was originally called Haddington Light Industries, but took the name of Ranco Motors when moved to a new factory in Hospital Road in 1958-59. A new line of products was undertaken building fractional horsepower electrical motors for the domestic appliances market. In 1965 the company was awarded a Queen’s Award for Export. Products and expertise expanded, and by 1969 the factory area had reached 65,000 sq ft, with a work force of 500. Amongst many other products, a large washing machine motor was being produced at the rate of 1000 a day.

In 1976, the Haddington part of Ranco was bought by the Scottish Development Agency, and the name was changed to LEMAC, the company being sold to Mycalex in 1981. There was a major addition to the product range in 1984, when the assembly of computer keyboards for IBM began, and by 1992 these were being made at the rate of 25,000 a week by 200 people. A management buy-out had taken place in 1988, with a further change of name to Lothian Electrical Machines Ltd. During the 1990s new products were introduced, but others, including the keyboard assembly, came to an end. The company continues to prosper, and Haddington residents have become used to seeing the new owner, John Jakes, arrive, piloting his own helicopter.

Robertson Brothers, engineers & blacksmiths, steam engineers, St Martins Gate, established their works in 1914. The brothers soon built up a reputation for inventiveness with steel products. Today, Robertson Brothers continue to apply these skills to many customers over Scotland and England, and have contracts with the lighthouse authorities and with distilleries, while their wrought iron work may be seen at many prestigious locations. A grandson of one of the founders continues to operate from a site close by the original workshops, and the firm continues to prosper with a workforce of ten engineers.

Starks Joinery Works/Stewart & Buglass; James Stark & Sons carried on high-class joinery and cabinet making at St Martin’s Close. Among the items manufactured were bespoke coffins for local undertakers. Sean Connery, before he became famous, was employed for a while as a French polisher. It was said that if he missed his bus home to Edinburgh he would make himself comfortable in a coffin for the night.

On the death of Jimmie Stark, the joinery shop removed to a site in Florabank, where the construction of large mobile homes for travelling showfolk, and showground booths, were a speciality. Stewart & Buglass continued this after taking over the workshops in the late 1960s, while their main service to the construction industry was installing ornate stairways and windows. The site is now being developed for homes, while Stewart & Buglass have workshops at the old railway station yard.

TD Precision Engineering was set up by Tommy Dodds, locating his precision engineering workshop in a tiny room on the West Mill site in 1972. Through hard work and long hours his services to the auto electrical, automotive, electronic and hydraulic industries were much sought after, and the business grew fast. Larger premises were needed, and a couple of sites were used as the workforce increased to 30 engineers, much of the work coming from the North Sea oil industry. In 1983, the firm moved back to a larger area at the West Mill site, which was fitted out to suit the requirements of precision engineering. Mr Dodds has now retired, but TD Precision Engineering continues to supply innovative products to the highest standard required in the modern world.

The East Lothian Courier (Haddingtonshire Courier to 1970); the Courier office narrowly escaped demolition during the war when a German pilot, having failed to reach his target, the Forth Bridge, jettisoned his bomb load over Haddington. The only one not to explode came to rest outside the back door of the office. The fact that it did not demolish the office was significant in a number of ways, not least because it ensured continuity of production that had gone uninterrupted since the first printing in October 1859.

After the war, and the lifting of restrictions on the use of newsprint, the newspaper continued as a mirror of East Lothian life, going from four pages to an average eight, and printing on a hand-fed press that required the better part of two days to complete the circulation of around 7000. Miss Evelyn Croal was editor, and her mother, Mrs J.G. Croal, chairman of the two-person board.

Most of the older employees had returned from the war and the working day, 8am ’till 6pm through the week and 8am ’till 12pm on Saturdays, was split between newspaper and jobbing print work. The Linotype casting machines that had been in place since early in the century continued to produce the hot metal type (used once, then melted for a further use) and the printing machines were no less robust. The first automatic press was bought in 1952, a platen machine that was excellent for all manner of small work.

In the boardroom changes were afoot. Mrs Croal was predeceased by her daughter and found herself in need of help. She turned to James Gray, one time printer’s devil, turned journalist, with whom she had kept in touch since he left Haddington. A limited company was formed with Mrs Croal as chairman and Mr Gray as managing director. Mr James Annand was the managing editor. When Mrs Croal died in 1956, Mr Gray took over the chairmanship, which he held until his death, when his son Allan took over. Sadly, he too died in 1974, and the chairmanship passed to Mr Kenneth Whitson, until then joint managing director with Mr Gray.

The Wharfdale that had been the means of producing the Courier over many years, with its attendant folder, gave way in 1964 to a Goss Rotary Press, capable of turning out 16 broadsheet pages at a single pass. By the late 1970s phototypesetting was making inroads into hot metal and a single keyboard was installed in 1979, launching, as it turned out, a new era for the office and the newspaper. Photopolymer allowed the simulation of hot metal from film generated type, and soon old machines like the Goss were enjoying a new life. Commercially the new technology proved to be a winner, and as workload grew through two recessions the staff grew too, from around 25 to the current 40.

Occupations – some recollections of work in the parish

Tradesmen’s wages were £5 per week; there were no paid holidays, they worked a 6-day week, including Christmas Day in Scotland. January 1 was a holiday.

Nessie Gell, c1945

Life as a stone mason/bricklayer, from the mid 1940s

Most people continued in, and enjoyed, the same occupation until retirement. I stayed in the same occupation for 56 years. It was a family building business (my uncle, then brothers). I became foreman and finally owned the business until I retired at 70.

As an apprentice – from c1945

At 14 years old, I was an apprentice, in my uncle’s building firm (Alex Moncrieff). This was a five-year traditional apprenticeship. The work was hard, watching the tradesmen, building under supervision and harsh criticism. Very particular standards of workmanship were expected; the youngest apprentice made tea over an open fire in drums (a washed-out syrup tin with wire for handles, blackened with much use). Tradesmen were helpful to the young ones, with a fatherly interest, and practical jokes! One lad was sent for a tin of tartan paint, and came back with cans of several colours – mix it yourself as you need it! From an apprentice you became a tradesman. The workforce tended to remain for years, and the foreman only left if he retired.

Hours and facilities

We worked a 46.5 hour week. The hours were 8am to 5pm with 30 minutes for lunch. Four hours were worked on the Saturday morning. We got two days off at New Year, and one week at the Edinburgh Trades – with pay. I was paid in cash, in a wages packet. I started at 12/6 (62.5p) then after some weeks got 15/- and there were no bonuses. I worked in the fields after 5pm for extra money. My wage packet was given to mother unopened to help with the family budget (I was the oldest of ten). There were no family allowances. You travelled to and from the job in your own (unpaid) time – taking 30 minutes each way, on the back of the builder’s lorry. Small ‘hap’ for the older men, the apprentices got on last, the foreman sat with the driver.

There were no arrangements for toilet breaks, or facilities. On an outside site we went behind a hedge or a wall as needed. Some householders didn’t seem to think the workmen had bladders! The apprentices had great fun at lunch times – hurriedly consuming their ‘piece’ to have games and contests – jumping, throwing brick the farthest, lifting bags of cement, or playing football. When working ‘in the country’ a great delight was waiting for the Co-op van to buy pies, crisps, lemonade and buns, which often the tradesmen would buy for the apprentices. Home baking from the farm cottagers’ wives was also much appreciated.

The work [included] building (council) houses, stone, brick walls, repairs (domestic and farms and estates), and stone fireplaces. The tools we used were trowel, mash, hammers, chisel, mason’s mell, plumb rules with lead ball spirit level, and a Rathbone 3ft folding rule. The work was self-satisfying. A ‘feel’ for stonework was essential for this – it was not just a job. The work was varied and interesting, and the camaraderie on site was good, probably because it was a small family run firm. The ‘Boss’ visited the sites daily in his car to check everything was done properly and to a high standard. We wore a brown bib and brace overalls (mason’s) as opposed to blue overalls (engineers, other trades) that soon became stiff with cement. They were not washed usually. Brown boots with yellow laces, and an old army greatcoat, and old tweed jackets were worn. There was not much provision for accidents or injuries though these were infrequent – there were not many falls off ladders. Eye injuries sometimes occurred from chips of stone or cement.

In those days, on Armistice Day (11am, 11 November) everyone had to stop work and stand in silence for 2 minutes.

James W. Moncrieff

Agriculture

Letham Mains | East Bearford

In the early 19th century, Haddington had the largest grain market in Scotland. Its role diminished after the arrival of the railways, and by the mid 1960s the grain market had closed, with the cattle market to follow a few years later. The principle produce of the farms, however, in the later decades of the century, was wheat, barley and some oilseed rape. There are almost 40 farms or parts of farms in the parish.

The farm of Letham Mains was purchased by the Department of Agriculture in 1936, and was divided into 26 smallholdings, each with a three-bedroom bungalow and shed, to enable people who could not afford a large farm to go into agriculture. (Another ten holdings had been created earlier at West Garleton, and 16 at Camptoun.) The products of the Letham holdings in the 1960s or 1970s included pigs, poultry, honey, canaries and West Highland terriers, roses and dahlias, besides white crops, fruit and vegetables. In later decades most concentrated on strawberries and raspberries, which were collected daily for the Edinburgh Fruit Market. Later still the practice of Pick-Your-Own was introduced, and now most of the land has been sold or let to a local farmer, while the house is occupied independently. One holding, however, now grows Christmas trees.

Many of the 40 farms in the parish experienced considerable change over the 55 years from 1945. The following account of East Bearford farm provides a fairly typical picture of agriculture in the parish; Caroline Lawrie has collated Robert C. Elder’s comments (see Farming by Fiona Dobson & George Barton, county volume).

East Bearford 1945 – 2000

Electricity | Crops | Apiary

East Bearford farm, of some 329 acres – a medium size for the area – lies at the eastern extremity of Haddington parish, almost three miles from the town. Originally part of the Wemyss estate, it was bought in 1944 by John S. Elder, of the fourth generation of his family to farm there.

The plain 19th century farmhouse, built of stone, harled in the 1930s, with a slated roof, faces north across a small field towards the road from Haddington to Traprain Law. In 1945 there were two semi-detached cottages beside the road, and behind them a row of three cottages. The oldest building was the grieve’s cottage, at a corner of the steading. The cottages and steading – comprising the traditional cart shed, byre, stables and cattle courts, with some other buildings – were all stone-built.

At this period ten men, including a grieve, worked on the farm, and extra staff were employed for harvesting. The five-day week was not introduced until 1968. Long hours were worked at harvest to take advantage of fine weather.

Electricity had been brought to the farmhouse and steading in the late 1920s – financially possible only because of the proximity of power at Traprain quarry. It was installed in the cottages in 1952. When it was proposed to enlarge and modernise the cottages in the mid 1960s, the planning department prohibited any alteration to the roadside facades, but allowed these two cottages to be extended at the back. As by that time the farm employed fewer people, the row of three smaller cottages was converted into one larger cottage and a double garage. The grieve wanted only a larger window for his house.

Alterations to the steading took place in the 1970s. The old cart sheds were replaced, as they could not accommodate the larger modern implements, or the height of tractors with cabs. The 19th century cattle courts were demolished and replaced by a single large covered area, suitable for housing cattle or grain – the traditional front, visible from the road, and the sides of the block being preserved.

Crops were grown in a seven-year rotation – grass, grain (wheat, barley, oats), and roots (potatoes, turnips, sugar beet), hay and other cattle feeds. Both sheep and cattle were fattened on the farm. Earlier there had been a herd of pedigree Large Black pigs – originating from some pigs that John Elder received in lieu of unpaid salary for managing the estate of a Gloucestershire peer, when he gave up that employment to farm on his own account. The herd became sufficiently well-known for a letter from overseas, addressed simply to ‘Mr Elder, Pig Breeder, Scotland’ to be delivered safely! Pig breeding had been discontinued before the end of the war, and black pigs are now a rare sight as the dark rind has made bacon from them unpopular.

Crops grown during the war had been regulated by the Agricultural Executive Committee, of which Mr Elder was a member, under the chairmanship of Major Broun Lindsay of Colstoun. Land that had lain fallow for generations was ploughed, and unproductive areas, such as golf courses, were brought into cultivation. Food shortages and rationing continued after the war, and for some time about 40 acres at Amisfield Park were rented from the Wemyss Estate, and worked from East Bearford.

An unusual aspect of East Bearford in the earlier part of the period under consideration, and before, was the apiary, begun on a small scale, but at its peak amounting to 200 hives, and in a particularly favourable year producing half a ton of honey. Clover and flower honey were produced locally, and some hives were moved to the Lammermuirs in July to gather heather honey. During the war years, honey had been the only really sweet thing that was not rationed; indeed the bees had their own sugar ration, so that the maximum amount of honey could be removed for human consumption, and sugar syrup fed to the bees in the winter. A large wooden shed near the back door of the farmhouse contained the equipment required to look after the hives and process the honey: sections were scraped clean and wrapped in cellophane, as were lighter weight pieces of comb, while the honey was extracted from the large frames and bottled for sale. Mr Elder and his family went to live in Edinburgh in the late 1940s, but the apiary continued for some years in partnership with a member of staff of the College of Agriculture. Until his death in 1958, Mr Elder attended market in Edinburgh, and sometimes had other business there, while motoring to East Bearford on the remaining weekdays.

There had been several tractors in use at the farm even before the war, and an early combine-harvester, towed by a tractor, was in use there by 1943. The last four farm horses were sold in 1954. Heavy machinery was very hard on the traditional farm road, and this was laid in tarmacadam for the first time in 1952.

In the 1950s, 60 cattle would be overwintered in the courts, then sold or put out to grass in May. In 1956 all were tested for tuberculosis – previously only the farm cows had been so tested. Potatoes were lifted by hand, and stored in straw and soil-covered pits outside. A potato-lifting machine was first used in 1964 (Mr Elder had himself been engaged in the design and testing of such machinery for some time). Grain from the combine was sold in sacks hired from the railway company, but in 1961 sheds containing a pit for unloading grain were built, and a diesel-fired drying plant installed. The following year storage bins were added, and grain was first sold by the ton and delivered in bulk lorries. 1961 also saw the sale of bunched wheat straw to cover the Murrayfield rugby pitch for protection from frost.

Andrew Ross, like his father before him, had long been grieve at East Bearford, and in 1960 he and his wife met the Queen at the Royal Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland’s Show, when he received his Gold Long Service Medal. His son, too, worked on the farm, and was also to qualify for the gold medal before he retired in 1991.

Several changes were introduced at the beginning of the 1970s. Large quantities of turnips had previously been grown to fatten cattle and sheep, but cattle feeding was now changed to barley, beet pulp and dried grains – an extract from the malting industry. Reversible ploughs were also introduced, and a shed built to store potatoes indoors. A novelty in 1976 was the sowing of turnip seed by helicopter, before the grain was combined. In 1979 potatoes were sold in boxes containing one ton.

Some disruption was caused by the laying of a gas pipeline from the St Fergus field to the north of England, which cut across the farm. There was also that year some exceptionally cold weather, when curling took place on the pond at adjacent Stevenson, on ice 10 inches thick.

Irrigation of potatoes began in 1984. Pipes and pump were used to take water from the river Tyne, on the north boundary of the farm, and from the Bearford Burn on the west. 1986 saw the first growing of oilseed rape – a crop that was to transform the appearance of the countryside in early summer.

Robert Elder (nephew of John), who had occupied the farmhouse since 1954, and had managed the farm for many years, retired in late 1991, and the farm was sold to Hugh Elder & Sons (Robert’s brother and nephews) of Stevenson Mains. By this date, East Bearford had been farmed by members of the Elder family for 140 years. Elders had also farmed at Stevenson Mains since 1889, and the two farms, divided only by the Bearford Burn, were now farmed in even closer conjunction than before. Some internal alterations were made to the farmhouse, where a dairy, and maid’s bedroom and bathroom were no longer required. The larger cottages were sold to owners unconnected with the farm, and the oldest and smallest cottage, which had been unoccupied for some years, was left in that condition.