Mining | Brickworks | Inveresk Gate | Agriculture | Other businesses

Industry

As both Inveresk Village and Whitecraig are essentially residential, it is at Wallyford that the greatest change in the economy can be seen. Agriculture continues on the land remaining unscathed by the housebuilders but in Wallyford the type of employment has changed radically from the days of the old pits and brickworks. New industries are provided by the industrial estate – built on the brickworks site; the old coal bings are now landscaped and houses have been built on the sites of the No.1 and No.2 pits.

Mining

For generations coalmining was one of the main industries of the village (see also four essays on mining in the county volume). The East Lothian pits were organised by the National Coal Board (NCB) into two groups, with offices at Wallyford and Ormiston; the Wallyford group took in Carberry colliery, which lay just outside the county boundary and into Midlothian.

Extensive early mining was carried out in the many shallow coal seams underlying Inveresk parish. Villages grew around the coal pits at various places, with the main ones left being Wallyford and Whitecraig.

Wallyford Colliery had closed for coal production before the war, being retained only as a pumping pit, employing 16 people in 1945. The miners of the village, however, could travel quite easily to the other Edinburgh Collieries Company pits at Carberry, Prestongrange and Prestonlinks. In 1945 Carberry employed 362 miners below ground and 133 above ground.

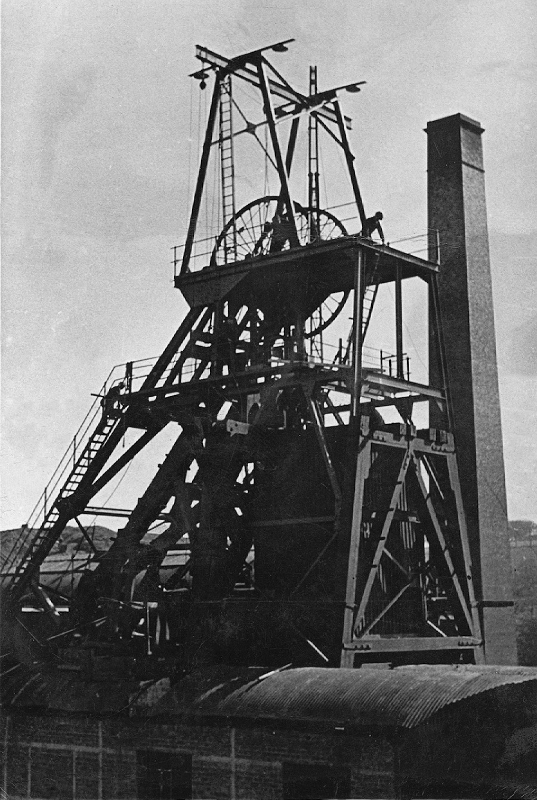

Carberry Colliery

Whitecraig village had basically developed to serve the A.G. Moore & Co. collieries of Smeaton and Dalkeith. Smeaton mines at Crossgatehall closed in 1948 but were replaced by the more modern and larger mines of Dalkeith Colliery situated near Smeaton Junction.

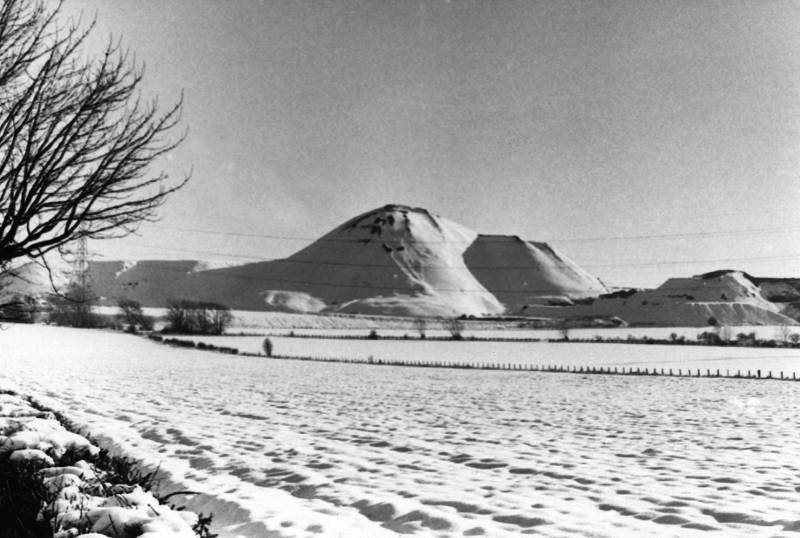

Smeaton Bing, pictured February 1978

Carberry, Prestongrange and Prestonlinks all closed in the early 1960s and Dalkeith in 1978 but by that time the National Coal Board superpits of Monktonhall and Bilston Glen were operational and absorbed the villages’ miners. The NCB from its inception in 1947 organised special bus transport to ease the travel problems arising from closures.

In 1977 the NCB gave the following figures for the number of miners living in the parish: Musselburgh – 209; Wallyford – 193; and Whitecraig – 91 (quoted in the West Sector Plan, 1978-81). In 1980 planning permission was refused for an NCB proposal to extract coal by opencast from Howe Muir, Wallyford. Revised plans (East Lothian Courier 1981 January 9, p1) brought a lively reaction from local community councillors, when they claimed that the NCB was ‘trying to steamroller over public opinion’.

Brickworks

Located between No.1 and No.3 pits, the Wallyford brickworks were part of the NCB’s operations from 1924-69 (Bourhill, p9). The works were then sold to the Scottish Brick Corporation; they closed in 1972, when employee numbers were c30.

James Burns was manager at the brickworks from 1960-72; in an otherwise undated and unattributed document held at Musselburgh Library, he described the process of brickmaking at Wallyford:

‘The red clay ‘blaes’, a poor quality clay, was brought in from various coalmines by rail and deposited outside. It was uplifted by mechanical shovel (Chayside) onto a conveyor belt, then fed into the crusher. The crusher broke the clay into pieces about 3″ in size. From there it was carried up into the mill where it was ground into dust, and then put through a screen. This dust was mixed with water in the ‘brick machine’. It was now ready to be pressed into bricks.

The brick table had 16 moulds around the outside. As the press came down into the mould, it formed the brick shape and printed ‘Wallyford’ on the brick. It was then pushed out as the table revolved and loaded onto a pallet by hand. Each pallet held 398 bricks, which were stacked into the kiln by forklift, but the last few pallets were stacked in by hand. The kiln entrance was then bricked up with ‘burn’ bricks and plastered with a mixture of sand and clay to make an airtight seal.

The kiln was gradually fired to a temperature of 1000º. This allowed the bricks to dry out first, before baking, preventing them from cracking. The whole process took around 11 days.

Wallyford had one continuous kiln which held around 11,000 bricks, and four square ‘intermittent’ hand-fired kilns which held between 25-30,000 bricks.

The bricks were transported by rail or lorry to wherever they were required. Over the space of time, Wallyford bricks were used in many buildings including some of the Boggs Holdings in Pencaitland and Wallyford Miners’ Institute’.

Located on the old brickworks site, the Wallyford Industrial Estate was established by the East Lothian District Council. Now run by East Lothian Council, by 2000 it provided accommodation for a range of businesses. These included ventilation contractors, car paint and lacquer suppliers and manufacturers, scrap metal merchants, floral and plant display and steel fabricators and erectors.

Inveresk Gate

In stark contrast, Inveresk Village was home to one of the most innovative industries of the modern era at Inveresk Gate. Its history spanned almost the entire period, before the firm moved to nearby Elphinstone over a lengthy period from 1965-95 (Woodward, F.N. 1985 pp60-73).

In 1944 the Scottish Seaweed Research Association (SSRA) was formed to consider the future of the seaweed industry in Scotland. Its accommodation at Edinburgh University was very basic; by 1946 Inveresk Gate (and its eleven acres) was purchased (£4500), and opened as SSRA headquarters by the then Secretary of State for Scotland, Joseph Westwood on 19 September 1947.

In 1951 the SSRA was re-named the Institute of Seaweed Research (ISR) and was entirely government-sponsored. Its laboratories were established at Inveresk Gate and employed around 50. Its last annual report appeared in 1955. Ahead of its time, the institute was researching renewable resources, non-food utilisation and bio-engineering.

In 1955 the American consultants Arthur D. Little were looking to establish a contract research laboratory in Europe (Woodward p81). In 1956 Arthur D Little Ltd, purchased Inveresk Gate; operating as the Arthur D. Little Research Institute, a British subsidiary, its first research projects began in 1957 and it was registered as a friendly society in the same year. In 1959 there were 31 staff and by 1963 that number was 62. In 1963, it became financially self-supporting.

The institute was beginning to outgrow Inveresk Gate and so in 1965 purchased the defunct Fleets pit bathhouse and fitted it out as the Elphinstone Research Centre. In June 1968 the Inveresk and Elphinstone research activities were merged and it was agreed that the ADL link would be severed – the British ADLRI taking over. The work was subsequently reorganised into three divisions – biological, chemical and physical sciences – and each of these divided into three sections. From April 1970 the business was renamed Inveresk Research International. The following year staff numbers were 100. The company began running clinical studies in 1975. The business continued to be run from both sites until December 1995, when the finance department finally left Inveresk Gate.

By 2000 the Inveresk Research Group had 2,300 staff across the world and had its headquarters in Edinburgh.

Inveresk Research works in partnership with a wide range of organisations worldwide providing services at every stage of product development. [It] has particular experience in taking new pharmaceutical products through pre-clinical (laboratory and animal-based work) and phase I-IV clinical (human) studies (Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures web page).

Agriculture

In the 1950s fruit farms, market gardening and nurseries were the dominant types of intensive agriculture in the parish; Pinkie Braes and Sweethope both specialised in market gardening.

Here Jim Braes, farmer at Barbachlaw, Wallyford, reflects on agriculture in the parish:

The main changes in farming in the Musselburgh area in the last 50 years are in the number of people employed in agriculture and horticulture.

Market gardening was a large part of land use in 1945 with many women, often miners’ wives, employed in the back-breaking work of planting and harvesting of vegetables, cabbages, cauliflowers, leeks, salad crops and turnips etc. In the 1950s the main markets were Edinburgh and Glasgow with Lowes of Musselburgh one of the biggest growers in the country.

Most farms also grew potatoes, either using local labour or Irish squads, the latter living in the most basic accommodation, sometimes just a shed divided by a partition between males and females. Some Irish families also came over in late spring staying on one farm until after harvest. They would start by singling turnips which, as the name suggests, meant ‘knocking out’ the extra plants to leave one every ten inches or so. They would finish after the potatoes were lifted and sorted. Gradually, with better roads, the local growers faced more and more competition from English growers who benefited from better climatic growing conditions.

Farms throughout the 1950s and 1960s had a mixed rotation consisting of grain (barley, wheat or oats) followed by grass for beef or dairy cattle, potatoes or turnips and then back to grain. Horses were still used in the 1940s and early 1950s with tractors taking over towards the end of the 1950s. The biggest change in machinery was the combine harvester, which changed the lives of many farm workers.

The larger farms had farm grieves (or foremen) who could hire and fire at will and were at ‘the top of the pile’. Beneath them, everyone had their place in the pecking order and woe betide anyone who stepped out of line. The first man had to be in and out of the stables first!

Mechanisation and the European Union changed the face of agriculture throughout the 1970s. The Irish workers became fewer in number during this time. Potato harvesters made light work of potato lifting and the numbers of farm workers dwindled. The advent of supermarkets and imported vegetables affected the fresh markets in Edinburgh and Glasgow and market gardening virtually disappeared in the area.

The expansion of housing around Musselburgh now covers large parts of Lowe’s farms. Surrounding farms, with the house now a hotel, swallowed up Scarlett’s market garden at Sweethope. Todd’s farm at Pinkie, once famous for egg production is now a shop.

Sweethope House, Inveresk

In 1976 market gardeners David Lowe & Sons, Musselburgh, closed after 116 years of trading. 175 employees lost their jobs.

Other businesses

At Newhailes, from about the 1960s, sections of the Newhailes Estate were taken over by housing and industrial estates. For many years there has been a nursery and garden centre run in the old walled garden.

J. & J. Mitchell’s (Newhailes) mink farm operated from 1949 through to the mid 1980s. The business was begun by John Mitchell and his father, John Snr and for many years they successfully exported pelts to Europe. In 1957 they had 2000 mink. By 1976 John and his brother David were experiencing a decline in business and it seemed likely to close, putting the five employees out of work (Musselburgh News 1976 January 9).