Stephen A Bunyan

The Civil Defence Corps was a Crown Service set up in 1949; it worked in conjunction with the TA. Its very existence provides evidence of the mood of the country during the 1950s; the Corps’ purpose was to provide a trained and organised body of men and women to undertake civil defence duties in a nuclear emergency. The strength of the movement in 1964 was 40,000 with intended expansion if war broke out.

Scotland was divided into three zones; East Lothian and Midlothian were in the eastern zone, with the City of Edinburgh, Berwickshire, Peeblesshire, Roxburghshire, Selkirkshire and West Lothian. Recruitment, organisation and training in the county were the responsibility of East Lothian County Council. The Military were also trained in Civil Defence and had role to assist the Civil Power if possible.

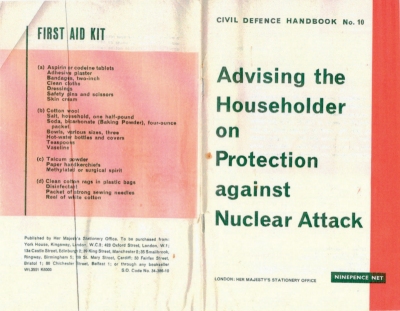

A booklet was produced by HMSO – Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack. It was available for purchase at 9d. (equivalent to 3.75p). The Civil Defence officers were to recruit volunteers. They were not paid, but there was an annual bounty of £10; the volunteers were provided with a basic uniform, which included a hard helmet and badges of rank, and a prayer book. Catering personnel in the welfare section were given a book of recipes.

Structure

The local division of East Lothian was divided into five sections, each of which had a range of responsibilities.

Headquarters Section had three sub-sections: Intelligence and Operations; Signal sub-section; Scientific and Reconnaissance.

The Warden Section was recruited and controlled by the police. It provided the link with the public, and was responsible for local reconnaissance reporting, deploying first aid etc. as well as reporting the degree of any fallout and controlling the public.

The Rescue Section was to rescue trapped casualties, and was trained in First Aid.

The Welfare Section was concerned with dispersal, the homeless, billeting, shelters, emergency feeding, and public information.

The First Aid Section rendered first aid and organised the removal of seriously injured casualties to ambulance pick-up points, where the Scottish Ambulance Service then took over.

In East Lothian

Recruiting in East Lothian was slow and continued to be on the reluctant side well into the 1960s; the initial target number was over 310. Training classes were held in Dunbar, North Berwick and Cockenzie. By the end of 1949, there were only 45 volunteers; in 1950, just over 100 came forward. The next year, the county total was 140 – Haddington had just 8. In 1954 the situation was still poor; of the 191 volunteers, 92 were male and 99 female. Training could only be carried out on a modified scale because of the low numbers.

In September 1958 there was a recruiting campaign; the County Council agreed to the appointment of an Assistant Civil Defence Officer. The numbers crept up to 218 by 1959, but more were still needed. This was far short of requirement even of a peacetime strength. The Civil Defence Officer Mr D Johnstone and his assistant Mr J Bain raised the number to 359 but more were needed in all sections.

In 1960 exercises were held to give practical experience of the likely aftermath of nuclear attack; again it was stressed that more recruits were required. In 1965 there were a number of serious accidents (some fatal) to site workers at the construction site at Cockenzie power station. The Civil Defence Organisation was asked to provide instruction in First Aid and rescue work. In April that year, East Lothian CD Corps won the national competition for scientific intelligence. The local usefulness of the team was demonstrated in May 1967 when the River Tyne came within inches of flood level and the CD were alerted. Beds were prepared in the Knox Clinic but the emergency never happened. Finally, in 1968 the 190 volunteers were told that the Corps was to be disbanded.

This came as a shock to the members; many were keen to continue on a voluntary basis without the annual £10 bounty, given if they completed 48 hours training in the year. But this was not possible because of the lack of facilities. Ironically, the CD HQ next to County Buildings, Haddington was being renovated at the time and garages to house the necessary vehicles had been built at Peppercraig Quarry, Aberlady Road (opposite The Vert) five years before. The roll book of the volunteers was given to the County Council so that they could be contacted if some need for their services arose.

The question has to be asked, why did the public not respond? In 1949 people were still war weary and fed up of austerity: they had done their duty for six years of war. There was no direct incentive. As usual, British governments expected to get volunteers on the cheap; the annual £10 bounty was, even then, hardly an inducement. The organisation, while worthy, lacked glamour; the training was bleak and the scenarios visualised were off-putting and unsettling. The public felt that nuclear attack was probably unlikely and if it did happen, the measures suggested would probably be ineffective. Possibly, in retrospect, they were right!